The mysterious quest to find the world’s lost soviet statues

- Text by Cristian Angeloni

- Photography by Neils Ackermann

Swiss photographer Neils Ackermann is no stranger to Ukraine and its people. He’s been living and working in the country since 2009. But after he published his first project, The White Angel – portraying life in Slavutych, the town built to host the victims of the Chernobyl disaster – he had no idea he would soon be heading to Chernobyl himself to look for Lenin.

On the night of the 8 December 2013, Ukraine was rocked by the Maidan revolution. The event saw the destruction of the red Lenin statue in central Kiev – a symbol of submission to the Soviets. Ropes, chains and hammers destroyed the communist icon into countless pieces. Lenin had fallen (again) – and his remaining 5,499 statues were about to fall all over Ukraine too.

As the memories of the events of the Maidan revolution began to fade, Neils and his colleague Sebastien Gobert started wondering what happened to those statues – and, as a joke, the two journalists started investigating their fate. They didn’t expect to end up in an artist’s courtyard, in a forest in the heart of the country and in a nuclear station.

In their new exhibition, Looking for Lenin, the Russian icon acquires a whole new visual meaning. Lenin is Darth Vader in Odessa, he’s radioactive in Chernobyl, and is a headless golden state in Shabo. Every aspect of the political figure is twisted and turned in a country doing its best to forget him.

In their new exhibition, Looking for Lenin, the Russian icon acquires a whole new visual meaning. Lenin is Darth Vader in Odessa, he’s radioactive in Chernobyl, and is a headless golden state in Shabo. Every aspect of the political figure is twisted and turned in a country doing its best to forget him.

“After the [Maidan] revolution, we quickly got bored of covering the war. I wanted to show other things about Ukraine,” says Neils. “We wanted to think more about the future and how to deal with the past.”

“We started our project in 2015, and we realised that the Kiev city administration, which is the legal owner of the statue, had absolutely no idea where it was gone. We found that the person who owned what was left of the statue was a businessman and art collector. We met his assistant; [the owner] was really reluctant to let us see and photograph the statue.”

The Kiev statue was only the beginning of a journey, with the journalists traversing all of Ukraine to document the relics of Lenin’s statues. For the book, they photographed around 70 lost Lenins – though they now claim to have found even more.

The Kiev statue was only the beginning of a journey, with the journalists traversing all of Ukraine to document the relics of Lenin’s statues. For the book, they photographed around 70 lost Lenins – though they now claim to have found even more.

“I was worried that photographing always these monuments could become boring, but quickly we realised that every single one was showing something different,” Neils adds. “We decided to photograph them only once they had been either toppled or destroyed. We photographed them once [their] propaganda role was disturbed.”

The statues were found, Neils says, in the most unthinkable places. “One was found by a friend of a friend who was renovating his house,” he remembers. “He discovered two busts of Lenin behind a wall. Another one was found by a colleague of a friend who works at Chernobyl. The power plant used to be called Vladimir Ilyich Lenin Nuclear Power Plant, and a two-metre high head of Lenin was installed outside the administration office. After the accident, they hid it in the building, but it disappeared 10 years ago.”

The removal of all communist emblems started in April 2015 with the “decommunisation law”, which banned the glorification of any Soviet symbol. Since then, monuments, streets and town names had to be changed or removed. “One of the biggest cities in the country, Dnipropetrovsk, had to be renamed Dnipro because of the soviet link to the word ‘petrovsk,’” Neils explains.

The removal of all communist emblems started in April 2015 with the “decommunisation law”, which banned the glorification of any Soviet symbol. Since then, monuments, streets and town names had to be changed or removed. “One of the biggest cities in the country, Dnipropetrovsk, had to be renamed Dnipro because of the soviet link to the word ‘petrovsk,’” Neils explains.

The statues, or what’s left of them, are now being reimagined by Ukrainian artists. “There is the visual example of the statue turned into Darth Vader in Odessa,” he adds. “One year they built a huge staircase [around the Kiev statue] that you could climb to the top and be your own statue. Others have some graffiti or Ukrainian paintings on them. These statues are becoming instruments to show how the Ukrainian identity is coming back.”

Neil and Sebastien’s book Looking for Lenin is out now, and the project is currently being shown at Les Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles until the 24th September.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

In Medellín’s alleys and side streets, football’s founding spirit shines

Street Spirit — Granted two weeks of unfettered access, photographer Tom Ringsby captures the warmth and DIY essence of the Colombian city’s grassroots street football scene.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Remembering New York’s ’90s gay scene via its vibrant nightclub flyers

Getting In — After coming out in his 20s, David Kennerley became a fixture on the city’s queer scene, while pocketing invites that he picked up along the way. His latest book dives into his rich archive.

Written by: Miss Rosen

On Alexander Skarsgård’s trousers, The Rehearsal, and the importance of weirdos

Freaks and Finances — In the May edition of our monthly culture newsletter, columnist Emma Garland reflects on the Swedish actor’s Cannes look, Nathan Fielder’s wild ambition, and Jafaican.

Written by: Emma Garland

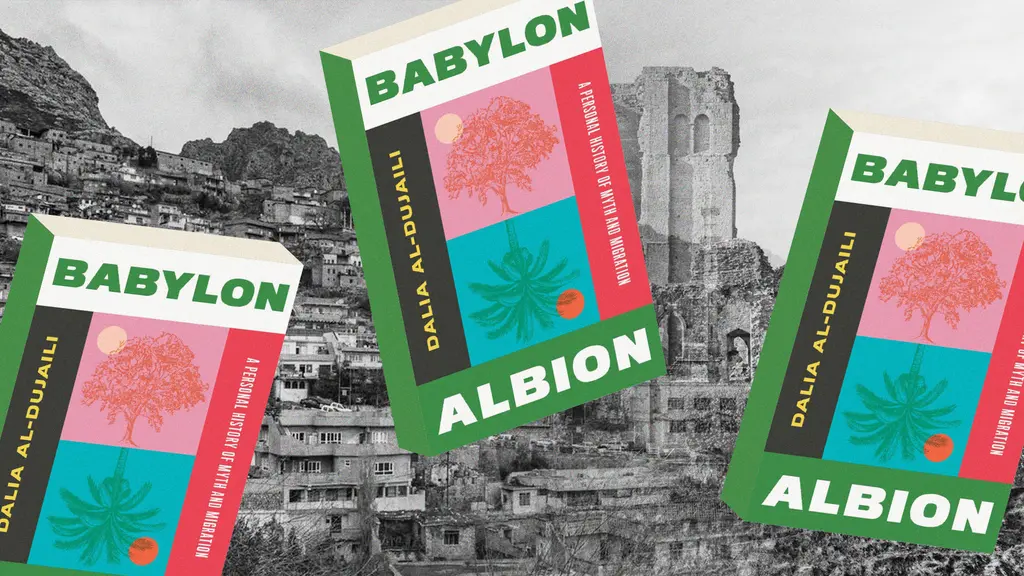

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Why Katy Perry’s space flight was one giant flop for mankind

Galactic girlbossing — In a widely-panned, 11-minute trip to the edge of the earth’s atmosphere, the ‘Women’s World’ singer joined an all-female space crew in an expensive vanity advert for Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin. Newsletter columnist Emma Garland explains its apocalypse indicating signs.

Written by: Emma Garland

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro