Poet Paul Hawkins raises the ghosts of East London’s ‘No M11’ squat protests

- Text by Joshua Gabert-Doyon

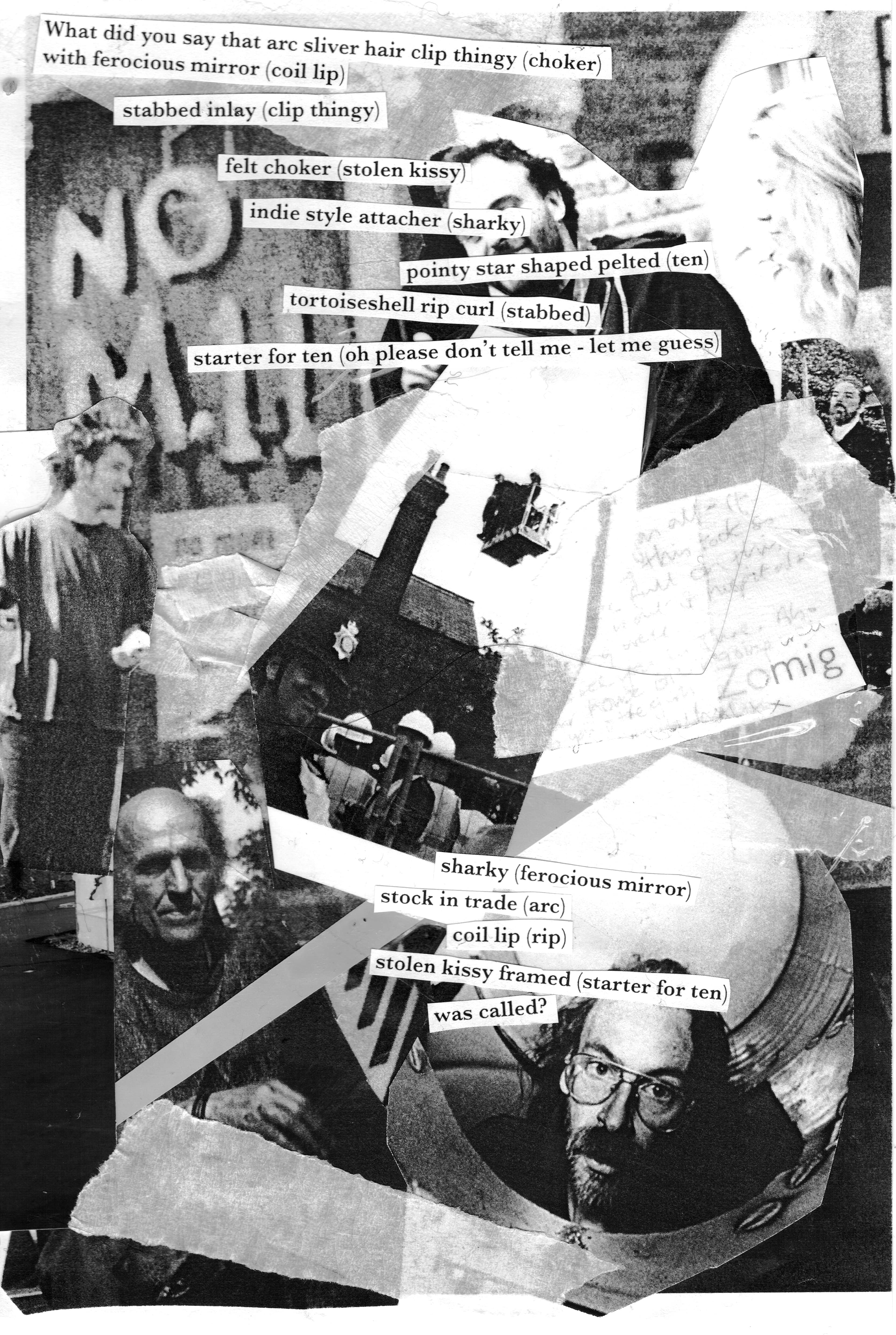

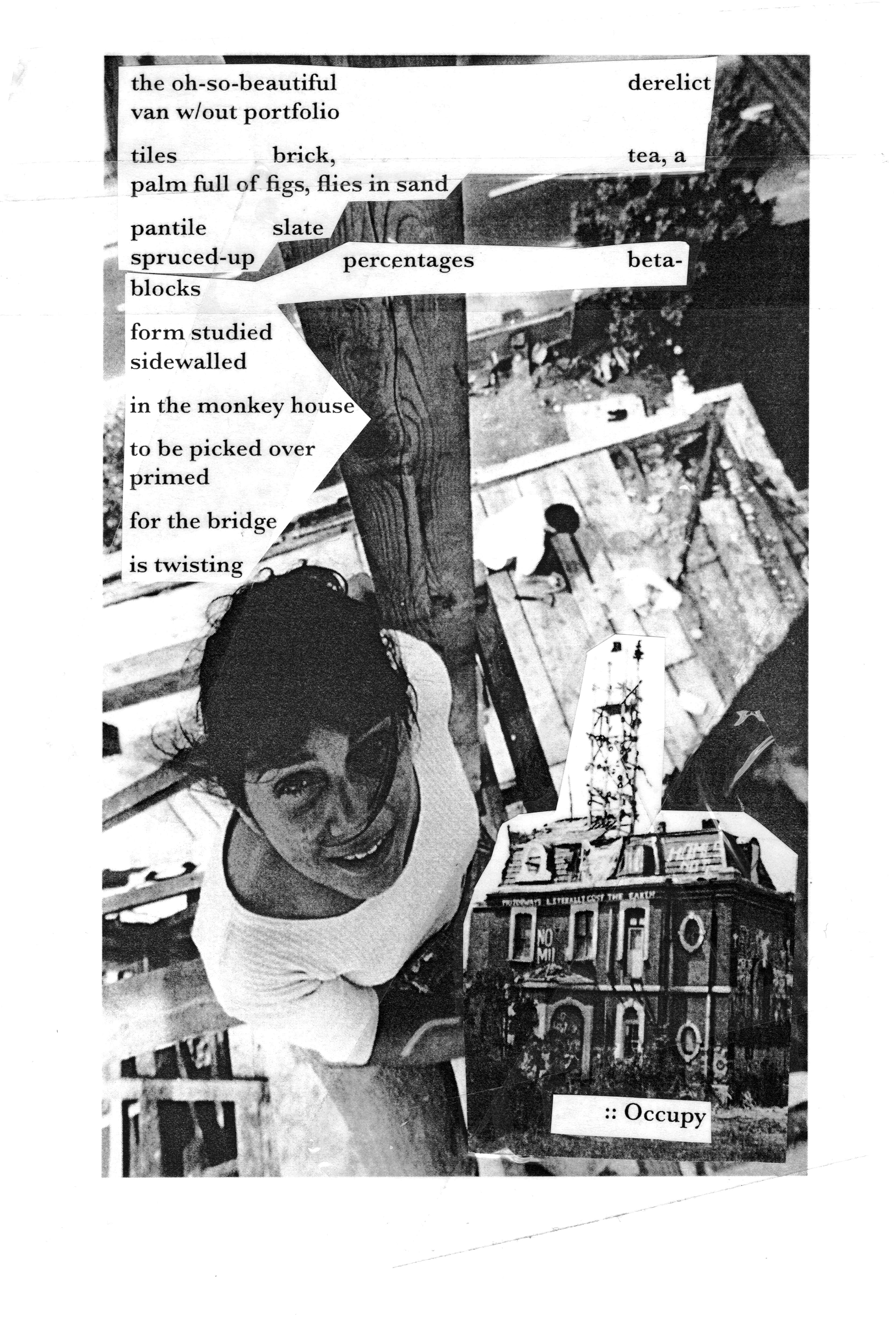

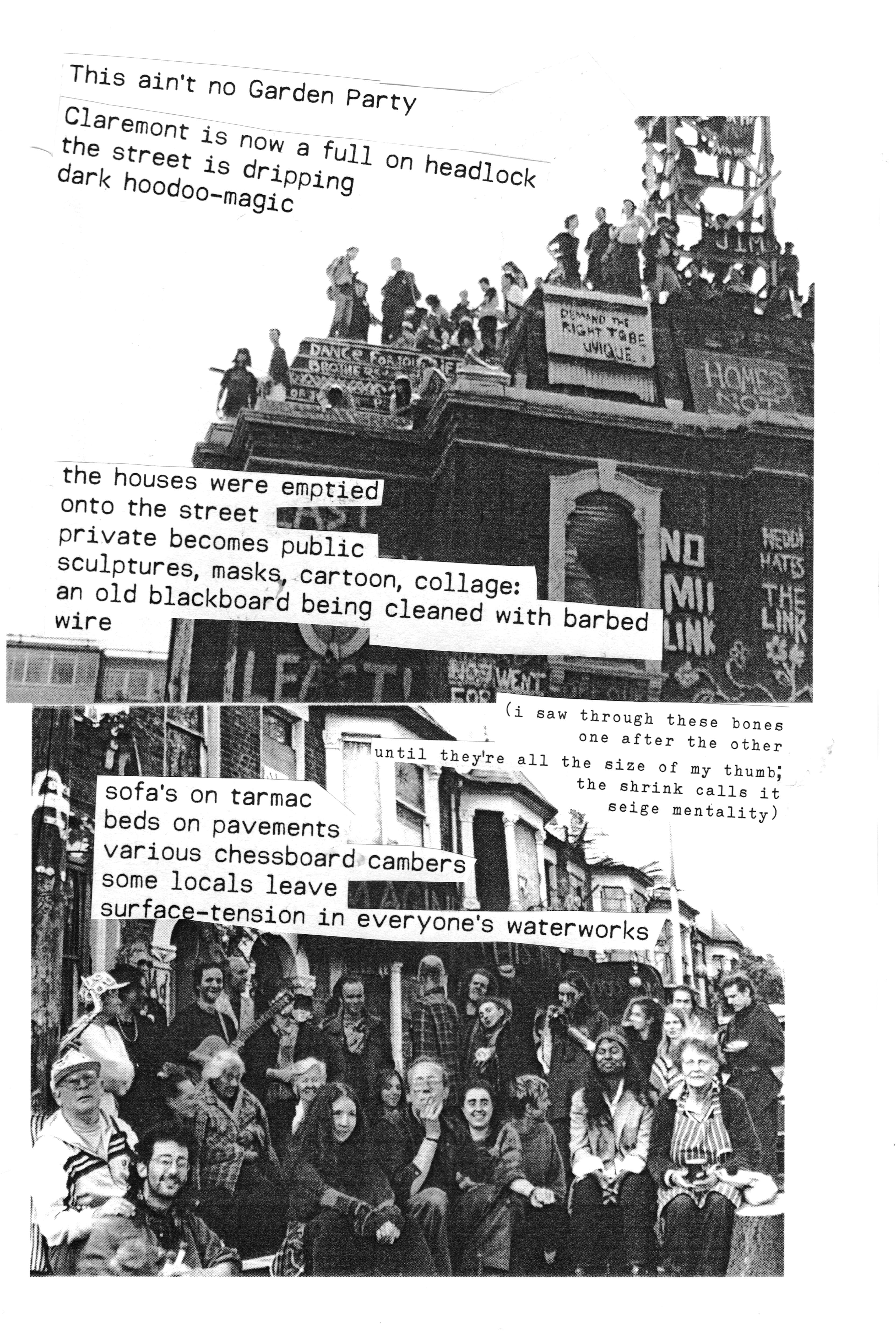

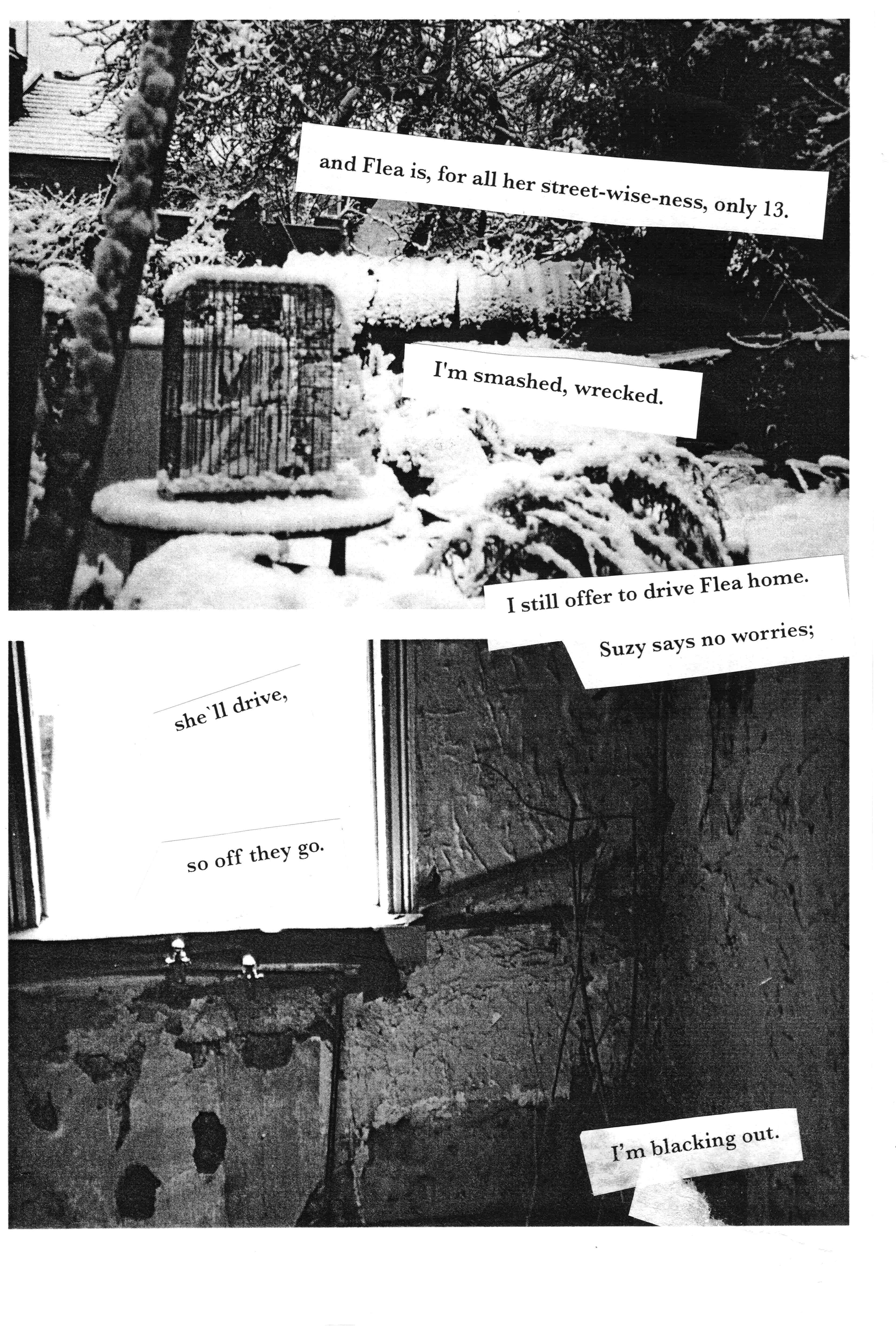

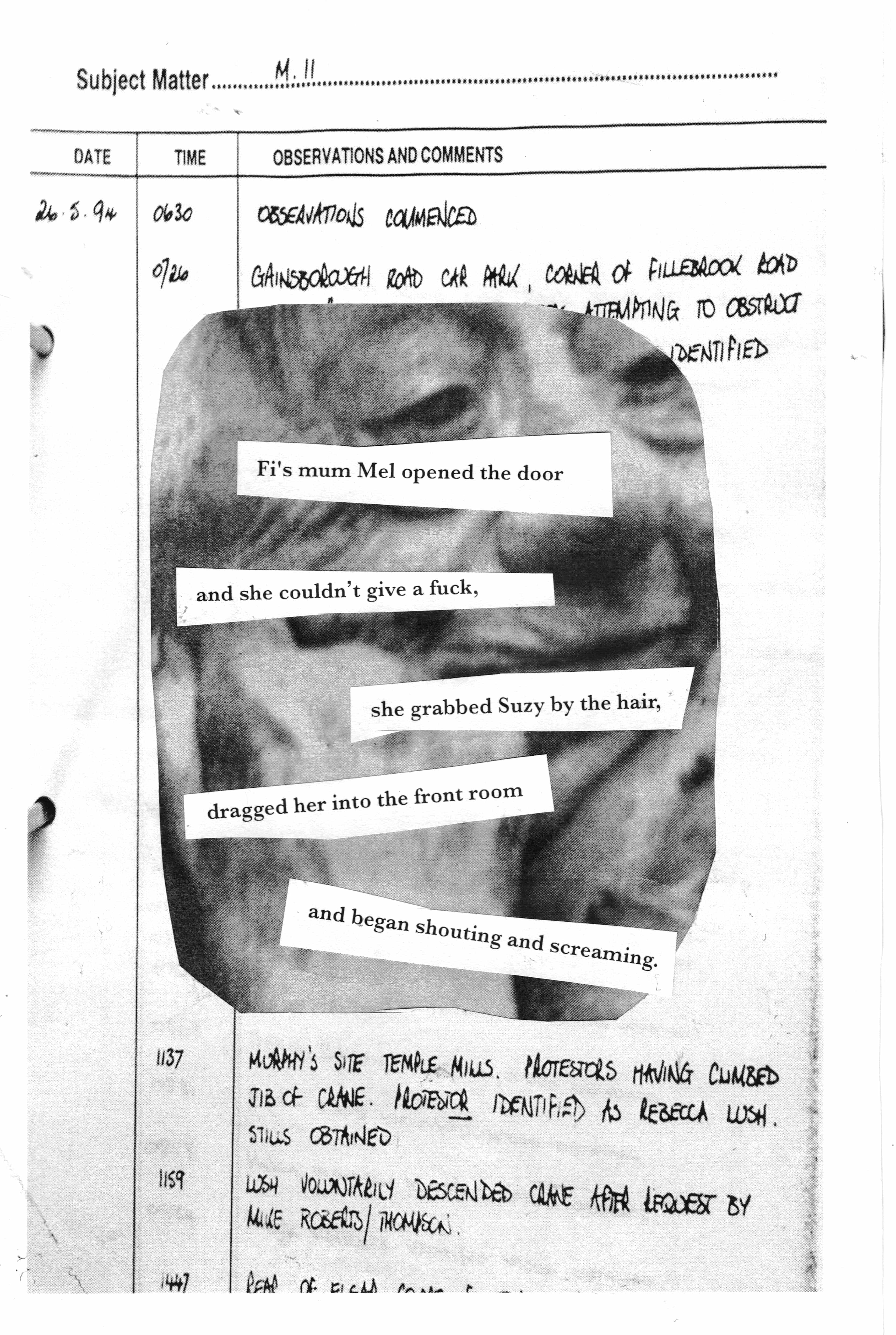

- Photography by Excerpt from "Place Space Dissent"

In the early-mid 90’s, when UK rave was getting started and punk was still fresh, a major development project was on the way: the M11 Link Road – connecting East London to the motorway. The roadway would pass through Leytstone, and lead to the demolition of large swaths of neighbourhood. It became the focus of significant protests, with squatters taking up residence in the houses earmarked for demolition.

The conflict came to a head on Claremont Road, where author Paul Hawkins was squatting. Hawkins’ latest book Place Waste Dissent, is a meshing of poetry, investigative journalism, and zine-style collage, featuring photos from the area, the protests, and of the people who lived on Claremont Road. Published by the London-based Influx Press, the book pushes at the boundaries of genre, telling the gritty east London story through the eyes of the residents. Huck spoke to Hawkins about the book and the Leytonstone protests.

How heated did the protests get?

Tempers frayed a lot. There were physical injuries. Friends would recall incidents of Police and security guard brutality, especially towards the end, in the last 6 months. People were up high in trees and on the roof. The authorities got pissed off with the protest – the strength, resilience and energy of the resistance.

But, remember I was squatting there until 1993, and then visited as often as I could . . . The demolition company Squibb and Davies were just as bad. Some of their ‘staff’ were thugs, not only in how they interacted, but in the intimidation, the smashing up of protesters vehicles during the night, the torching of a bender at the George Green site, in which people were sleeping – these are just a few examples.

The integration of official documentation – eviction notices, police reports – is really well done in the book. They offer this sort of counterpoint to the lived experience of Dorothy (who lived on Claremont Road since her birth in 1901, and became an ally of the protesters). Can you talk a bit about your approach to balancing the different narratives?

Thanks. I wanted to produce something lived, as you noted, something concrete too, and the use of form in poetry is really important to me. I like to create text that moves away from more traditional forms, like sonnets, haiku, quatrains or tercets. Not that there’s anything wrong with these forms, it’s just that they feel so dated sometimes; so very academic, and the subject matter, the emotional drive behind the writing was something that was of the 21st century, here and now, of immediacy, as well as contradiction and confusion. Hence some poems in the form of official documentation.

What was the research process like for this book – can you describe the experience of revisiting these stories?

It was emotional. Tiring. Shocking. I gathered many cuttings, photos, articles, etc. whilst squatting in Claremont, and continued to do so over the ensuing years. Some of these prompted a pamphlet collection of poems called Claremont Road in 2013. When Gary and Kit at Influx Press gave me the go-ahead for the book, I realised I needed a lot more than memory to rely on. I went to The Museum of London where there’s a big archive of ‘No M11 Link Road’ protest stuff and dipped into that all day.

Watching the documentaries Blight by ‘No M11 Link Road’ protestors John Smith/Jocelyn Pook, and Housewatch by Claremont Road resident Ian Bourn was really helpful as a prompt for getting ideas down. Like a lot of others, I played in bands when squatting there, and just listening back to rehearsal tapes and a live CD we made at one of many benefit gigs was really helpful too.

I went for a walk with my partner Sarer Scotthorne and Gary Budden (editor and 50% of Influx Press) along the whole of the route filming, taking photos and talking about what I remember happening, almost non-stop along what was eventually built: the A12 extension.

The research process was long, and, at times, exhausting – a lot happened along the route, not all of it very pretty. I touched base with Alice Nutter, who had undertaken extensive research of the protest with a view to writing a play about those times, which may still see the light of day, and she reminded me of some challenging times that I’d forgotten about. Shit happens.

The blending of forms – poetry, and collage zine-making stuff – can you talk a little bit about the decisions you were making with that?

I was hugely influenced by the cut-up process; from Tzara, to Gysin/Burroughs and the late David Bowie. Their text experiments were powerful. I also really liked a book by Laura Oldfield-Ford called Savage Messiah, Anmiel Alcaly’s Neither Wit Nor Gold, and fanzines in general.

They all used an approach of scuzzy xeroxed black and white images, cut and stark, pasted typewriter text, drawings and signs. I love the immediacy and roughness of these styles, and so wanted to have a go myself.

I was really helped though by the use of images by Julia Guest, Maureen Measure, Steve Ryan and Sarer Scotthorne in the book. Those photos were simply stunning, and really made the book. I wanted to include everything.

Can you describe the intersections between the environmentalist movement and the squatting that was going on? Place Waste Dissent takes an interesting turn towards rocks and earth at one point near the end of the book…

There were big connections made between environmentalism and implications of mass road-building. The choking planet; Homes Not Roads. Thatcher’s 1989 Roads For Prosperity White Paper (2,700 miles of new or improved road to the trunk road network and 150 new bypasses) was very short-sighted, served the interests of big business and industry, and ultimately very foolish to announce.

The protest movement grew; Twyford Down, The M11, Solsbury Hill and many more, grew out of a sincere fear of the pollution and waste, as well as a growing hatred of the Thatcher/Major axis; things like The Poll Tax, inequality, the housing crisis, and the Criminal Justice Bill. People realised so much was at stake, and that gave a renewed energy to protest together. The original Roads For Prosperity plans were eventually dropped. These problems still continue today, however.

If you try and fix the flawed, corrupt, wasteful, undemocratic, broken project called capitalism, things will never ever improve.

Paul Hawkins’ Place Waste Dissent, is published by Influx Press.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Love and rage at the record shattering London Trans+ Pride 2025

Dismantle the cis-tem — With over 100,000 attendees, the Saturday march was the largest trans pride event ever in world history. Cheer Up Luv’s Eliza Hatch captured the action, and recounts its powerful energy.

Written by: Eliza Hatch / @cheerupluv

In 2025, festivals have become defiantly political. Roskilde is one of the most powerful

A sea of people — Music and countercultural movements have a hand-in-hand relationship spanning decades. As authorities increasingly police traditional on-street protests, dancefloors and crowds are again becoming crucial spaces for solidarity, writes Ella Glossop, reporting from Denmark’s largest festival.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Remembering the radical anti-nuclear Greenham Women’s Peace Camp

Life at the Fence — In the early ’80s, a women’s only camp at an RAF site in Berkshire was formed to protest the threat of nuclear arms. Janine Wiedel’s new photobook revisits its anti-establishment setup and people.

Written by: Miss Rosen

In photos: Hundreds gather outside court to protest Kneecap terror charge

‘Free Mo Charah’ — With drums, smoke and applause, protesters greeted the rapper outside court as he was released on unconditional bail.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong tells ICE to “fuck off” in LA protest video

Saviors — The singer shared the post on Sunday, featuring the band’s recently released song ‘Fuck Off’ as its soundtrack.

Written by: Isaac Muk

A reading of the names of children killed in Gaza lasts over 18 hours

Choose Love — The vigil was held outside of the UK’s Houses of Parliament, with the likes of Steve Coogan, Chris O’Dowd, Nadhia Sawalha and Misan Harriman taking part.

Written by: Isaac Muk