In Photos: The secret gay language still in use today

- Text by Josh Jones

- Photography by Felix Pilgrim

“I like zhoosh,” says Professor Paul Baker on his favourite Polari word when we interviewed him for this feature. “It’s got an interesting pronunciation and starts with a consonant sound that rarely appears at the start of words in English (the “zhju” sound), although you do get it in languages like French, so it’s a word that sounds exotic to English ears. You have to place your mouth in a certain position to get the sound right, sort of pouting your lips and putting your top and bottom sets of teeth quite close together, so you make your face quite camp when you’re saying it.” Professor Baker knows what he’s talking about. Not only is Paul a professor of English Language at Lancaster University, he’s recognised as the world’s foremost expert on Polari – his book, Fabulosa!, is a must read if you want to discover more about the language.

“It’s also a very versatile word,” he continues. “You can zhoosh your riah (do your hair) or slap (make-up), zhoosh a bevvy (have a drink) or even zhoosh the dinarly (steal the money). I was in a gay pub last night and someone used the word “zhoosh” when talking to me, so I do still hear bits and pieces of it now (they probably got it more directly from Queer Eye, an American show, although it is still Polari). So there are some words from it that are still used on the gay scene, although it is not used to talk in full sentences as it was used in the 1950s.”

Can you give us an abridged history of Polari, professor?

It’s very hard to get a complete history of Polari because it was a secret spoken language, rarely written down, and developed before the availability of audio recording devices. In the 18th century groups of men who had sex with men – known as Mollies – were using slang terms like ‘bitch’, ‘queen’ and ‘trade’, and they also sometimes used forms of Cant, a slang used by criminals of the time. From today’s perspective, some of the Mollys might be seen as non-binary or trans, although identities were understood differently back then. As we go into the 19th century we start to see a newer form of slang, called Parlyaree, which was used by Italian entertainers in the UK. It was also used by beggars, circus and fairground people and travelling markets. It included bits of slang used by sailors who travelled round the Mediterranean. Gradually, Parlyaree made its way into music halls and then theatres, becoming more adopted by gay dancers and actors and male sex workers. By the early 20th century this newer version of Parlyaree was known as Polari, and it had been supplemented with various words and phrases that were of relevance to gay men, as well as some of the old Molly words. It was popular in UK towns and cities with gay scenes until the 1960s, when decriminalisation of homosexuality meant the need for a secret language was less important.

How did it become influenced by so many different cultures to end up being what’s commonly referenced as “a secret language for homosexuals”?

The simple answer is that people can belong to more than one culture, and different cultures rarely operate in isolation from the rest of society, so there is usually crossover. The cultures that used Parlyaree and then Polari had a few things in common – they contained people who tended to travel around a lot, and were on the fringes of society, often at risk of being arrested. Until the end of the 18th century, actors were not seen as a respectable group. So for these people there was a need to communicate things in secret, for protection.

The people and cultures who’ve influenced and added to Polari would not have been regarded as mainstream – did this influence how the language developed?

Yes, many of them lived day-to-day, their lives could be unpredictable and sometimes even brutal and violent. They had little opportunity for social advancement and they were not usually highly educated. In a sense, they were beyond the restrictions of refined society, and for those who had gay or lesbian sex, that made them criminals. Many of them used taverns, pubs (or later on bars and drinking clubs) as places to meet, so alcohol was part of the culture, as was a somewhat matter-of-fact approach to sex – very un-Victorian!

How important to the queer community was Polari – especially pre 1967 – it was a genuinely unique language of a subculture.

I doubt that if you invented a time machine and went back to the 1950s and asked people if Polari was important they would have said it was – they didn’t have the perspective we have from the 2020s, they were just getting on with their lives, making the best of things, not being impatient and angry because they didn’t have legal status or laws to protect them. Polari was just a normal part of everyday life to them. But it did offer a form of protection, and a way of communicating shared values and humour, allowing them to bond and also to identify one another at times. So I’d say it was important, although I think some of them might laugh at the idea that something like Polari is even of interest to social historians.

When was Polari in use the most with the queer community?

You’d have heard it in gay pubs and bars, as well as being spoken on cruise ships where lots of gay men worked, up until the 1970s. You might also hear it in cruising areas: cinemas, Turkish baths, parks and public loos, although it might be more of a hissed warning: “Lily!” when the police were spotted. And you might hear it on public transport so that two people could have a conversation without others understanding.

Kenneth Williams’ popular radio show in the ’60s famously used Polari in its scripts. Was that a good or bad thing? Did the exposure of it to the mainstream kill it off?

Round the Horne provides a record of Polari which, although scripted, was created by people who knew what they were talking about – Kenneth Williams who played Sandy, used Polari himself among his friends and in his diaries. And the sense of humour from Julian and Sandy is very much in keeping with those who used Polari. It did expose the secret to large numbers of people so hastened its demise a bit, but I also think that by the late 1960s, Polari had already started to go out of fashion, and if anything, the radio show revived it for a short while in the gay scene.

How near is it to dying off – are there any projects to bring it back or help it survive?

I’ve been involved in lots of projects to commemorate or remember Polari, but none really to bring it back. Artists and script writers have done all sorts of amazing things with Polari in the last 20 years or so. It is important to remember gay social history and Polari has the capacity to capture imaginations, especially young queer people for whom everything is new. I was captivated by hearing Polari spoken by Julian and Sandy when I listened to theRound the Horne audio tapes back in the ‘90s. And now, when I type “Polari” into TikTok, it’s always nice to see a young person saying “Hey guys, did you know there used to be a secret language called Polari!” It’s great that so many younger people find it interesting and fun and want to share it with one another. So there is a continuous process of rediscovery for each new generation, and thanks to the internet, it’s much easier to find out about it than it used to be, even though there are fewer of the original speakers left.

This piece appeared in Huck #80. Get your copy here.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Support stories like this by becoming a member of Club Huck.

You might like

Largest-Ever Display of UK AIDS Memorial Quilt Opens at Tate Modern

Grief Made Visible — Comprising hundreds of panels made by lovers, friends and chosen family, the UK AIDS Memorial Quilt returns in full for the first time since 1994 – a testament to grief, friendship and the ongoing fight against HIV stigma.

Written by: Ella Glossop

In Medellín’s alleys and side streets, football’s founding spirit shines

Street Spirit — Granted two weeks of unfettered access, photographer Tom Ringsby captures the warmth and DIY essence of the Colombian city’s grassroots street football scene.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Remembering New York’s ’90s gay scene via its vibrant nightclub flyers

Getting In — After coming out in his 20s, David Kennerley became a fixture on the city’s queer scene, while pocketing invites that he picked up along the way. His latest book dives into his rich archive.

Written by: Miss Rosen

On Alexander Skarsgård’s trousers, The Rehearsal, and the importance of weirdos

Freaks and Finances — In the May edition of our monthly culture newsletter, columnist Emma Garland reflects on the Swedish actor’s Cannes look, Nathan Fielder’s wild ambition, and Jafaican.

Written by: Emma Garland

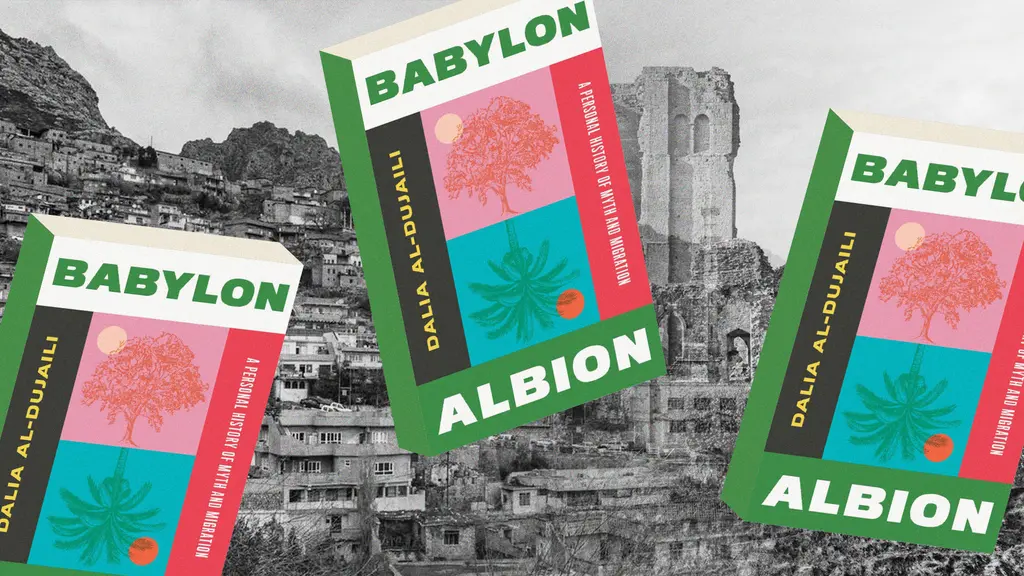

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro