Revisiting London’s East End During the ’70s and ’80s

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by Bandele ‘Tex’ Ajetunmobi

In 1947, self-taught photographer Bandele ‘Tex’ Ajetunmobi (1921–1994) stowed away on a boat bound from Nigeria to Britain. After a post-polio disability rendered him estranged from his own community we was determined to build a new life for himself.

Ajetunmobi settled into East London amid a broad swath of émigrés from all across the Global South. Over the next five decades, he chronicled the world in which he lived, crafting an intimate portrait of the East End as seen through the perspective of a consummate insider.

Operating a market stall in Brick Lane placed Ajetunmobi at the nexus of street culture as it took root during the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s, providing him with an unparalleled vantage point. Ajetunmobi’s work reveals a profound sense of solidarity among the working class, forged through the shared struggles and celebrations that are the marker of community.

“The postwar migratory story of Britain is often seen through the lens of conflicts, riots, and racists attacks, but a lot of the story is the everyday encounters where people work together and the relationships they have,” says Dr. Mark Sealy OBE, Executive Director of Autograph, who has curated the new online exhibition, Bandele ‘Tex’ Ajetunmobi: Street Scenes from the East End, 1950 – 1980.

“This is a time when things happening on the peripheral become the matrix of London,” Sealy says. “The working class are the frontline of diversity; the poor live side by side and have to get along. The undercurrent of Tex’s work is a city in transition.”

As chronicler of modern life, Ajetunmobi readily photographed friends and acquaintances he happened upon on the streets, pubs, and homes dotting Whitechapel, Stepney and Mile End, crafting a layered tapestry of East London life.

“There is a difference between someone arriving in a community and wanting to document it, and someone being in the community who happens to have an enthusiasm for the camera, and what it can do. The landscape is not something you go and discover, it's something that you're in. There’s a degree of intimacy that begins to reveal in image after image after image,” says Sealy.

“In many ways, this is a visual diary. I wouldn't say it's a documentary; it's more about this is what I'm seeing, and this is who we are. Sometimes people have an intuitive sense, like a musician, to build a rhythm of what's actually going on and it's not for profit or any kind of cultural gain. It's simply to speak to that place.”

Following Ajetunmobi’s death in 1994, most of his work was destroyed, save for some 200 negatives and camera equipment now in the collection of Autograph.

“I think the story of photography is not necessarily the story of the heroes that we know about,” Sealy says. “The story of photography is all of those people like texts, all of those cameras, all of those moments are those boxes under the bed, or those castaway images.”

Bandele ‘Tex’ Ajetunmobi: Street Scenes from the East End, 1950 – 1980 is on view online at Autograph in London.

Enjoyed this article? Follow Huck on X and Instagram.

Support stories like this by becoming a member of Club Huck.

You might like

Remembering New York’s ’90s gay scene via its vibrant nightclub flyers

Getting In — After coming out in his 20s, David Kennerley became a fixture on the city’s queer scene, while pocketing invites that he picked up along the way. His latest book dives into his rich archive.

Written by: Miss Rosen

On Alexander Skarsgård’s trousers, The Rehearsal, and the importance of weirdos

Freaks and Finances — In the May edition of our monthly culture newsletter, columnist Emma Garland reflects on the Swedish actor’s Cannes look, Nathan Fielder’s wild ambition, and Jafaican.

Written by: Emma Garland

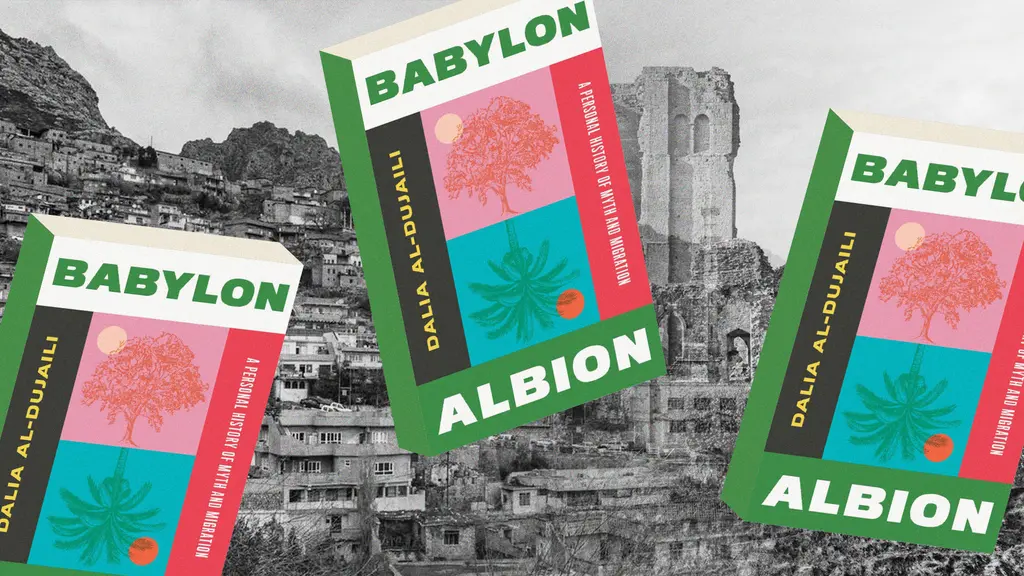

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Why Katy Perry’s space flight was one giant flop for mankind

Galactic girlbossing — In a widely-panned, 11-minute trip to the edge of the earth’s atmosphere, the ‘Women’s World’ singer joined an all-female space crew in an expensive vanity advert for Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin. Newsletter columnist Emma Garland explains its apocalypse indicating signs.

Written by: Emma Garland

Katie Goh: “I want people to engage with the politics of oranges”

Foreign Fruit — In her new book, the Edinburgh-based writer traces her personal history through the citrus fruit’s global spread, from a village in China to Californian groves. Angela Hui caught up with her to find out more.

Written by: Angela Hui

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro