Skateboarding through China’s Wild West

- Text by D'Arcy Doran

- Photography by Terry Xie

Stepping off the plane in Ürümqi, the capital of Xinjiang, from anywhere else in China is disorienting. The first thing you notice is the faces; taxi drivers who would look at home in the Mediterranean offer to take you where you need to go. Next you notice the light; here sunrise is at 8am and ‘noonday’ doesn’t come until after 2pm, as the sun refuses to obey the clocks set by rulers two time-zones and 3,000 kilometres away in Beijing.

Then there is the dawning realisation that you are now at the furthest point on Earth from any sea in this territory bordered by Mongolia to the north, Tibet to the east and Afghanistan and Kashmir to the west.

Xinjiang (pronounced Sin-jang) means new territory in Chinese and through accident and ambition it finds itself an autonomous region on China’s far west frontier. The territory’s Muslim ethnic Uyghur majority calls it East Turkmenistan. Officially, China says it has controlled this vast expanse of desert, mountains and steppe since 60 B.C. “It would be more accurate to see it as an occupied country undergoing its sixth or seventh invasion from China in two millennia,” Christian Tyler writes in his book Wild West China.

Over that time, it has been been a pivotal point on the Silk Road trading route that linked emperors from Beijing to Rome. At various points, Tang dynasty armies, Mongol conquerors, Qing emperors and Tajik adventurers have fought each other for control. Xinjiang has long captured China’s imagination. For author Wang Dulu, who wrote Chinese ‘westerns’ in the 1930s, including Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Xinjiang’s desert plains were where tribal bandits waited to ambush Chinese officials’ stage coaches.

Terry Xie was twelve when he first learned of Xinjiang’s existence in geography class in Nanjing, on the other side of the country. The details were textbook facts; fuzzy contour lines that didn’t connect to form an image – deserts, mountains and minorities who eat barbecued lamb.

But as he grew older, that incomplete picture became an itch he needed to scratch. He was intrigued by the Islamic culture – the people, music, clothing, architecture – that seemed a world away from his Han heritage, China’s predominant ethnic group. “I definitely had to pay a visit to the largest Islamic community in China,” he says. “I wondered about its [supposed] ‘otherness’.”

An avid skater, Terry, now thirty, became a professional skateboarding photographer. He was covering a competition in Shanghai when he heard there was a Xinjiang skater competing named A-yong. He tracked him down. They couldn’t speak for long due to Terry’s work, but the photographer told A-yong that he would love to come to Xinjiang so they could hang out.

Since Terry’s childhood discovery of the new frontier, the attacks of 9/11 and their aftermath had transformed the way China’s state-controlled media portrayed Xinjiang. Any Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon romanticism faded. The sense of adventure was replaced by fear.

For decades, Beijing had been trying to make Xinjiang more Chinese by encouraging Han settlers to immigrate west, enforcing religious controls and demolishing traditional Uyghur buildings to make way for modern high-rises in the name of economic development.

Many Uyghurs chafe at what they see as attempts at assimilation and a small number want independence. Chinese authorities seized on George W. Bush’s ‘war on terrorism’ to justify cracking down on protesters and ‘religious extremism’ in Xinjiang. State media, and state broadcaster CCTV in particular, helped make Xinjiang synonymous with terrorism.

“Most Chinese people do think of that place as unstable, unsafe, not being friendly to the Han,” Terry says. “I wanted to discover stuff that was different from what we see on TV.”

Terry contacted A-yong to say he was coming to see life on the new frontier for himself.

In the capital Ürümqi, A-yong ran Street Life, a skate shop and hub for young skaters just wanting to hang out. It became a window into the community for Terry. He met another skater named Elee through Weibo, China’s answer to Twitter, who also offered to introduce him to Xinjiang’s skate community. Among the skaters, Terry found Han and Uyghur teens hanging out together, joking in Mandarin – which Uyghurs must learn in school. They would skate, snack curbside on barbecued lamb skewers, aka ‘chuars,’ and try to steer clear of a common antagonist: Xinjiang police.

“Cops in Xinjiang are way tougher because of the instability in the area in recent years,” Terry says. “You are not allowed to carry a skateboard with you when entering public parks. Skating there is impossible! You can only skate in the streets with few people.”

His Uyghur skater friends even gave him a nickname, ‘Abdullah Terry,’ which he adopted as his WeChat profile. They would also call him ‘Aghine’ – slang in the Uyghur Turkic language for ‘like-minded brother’.

“Most Chinese people do think of that place as unstable, unsafe, not being friendly to the Han. I wanted to discover stuff that was different from what we see on TV.”

“The purpose of the first trip to Xinjiang was as simple as hanging with friends, experiencing Islamic culture and maybe shooting some skateboarding photos, if we found any interesting spots,” he says. “Only after I actually went there, I found that there are surprisingly many young people who are passionate about skateboarding. When I was hanging and skating with them, the idea of shooting the Aghine project just hit me. Why not take portraits of this young group of people to let the world know about their existence?”

The Aghine project would be a series of portraits of Xinjiang skaters from different ethnic groups, who skate together not caring about race or religion. The series and resulting photobook, shot over two trips, is Terry’s attempt to help rebalance the negative perceptions in the rest of China towards Uyghurs and Xinjiang’s other ethnic minorities.

“It is a melting pot of different styles,” Terry says. “Han teens would take their style inspiration from Korean and Japanese fashion while the Uyghurs were influenced by Turkish trends. American street style, although often a year or two behind, is popular with all. Hip hop, electronic and rock music spilled from all the skaters’ headphones, with Uyghur skaters having a soft spot for Turkish tracks and Uyghur pop.”

“They don’t give a damn about politics,” Terry adds. “Skaters, all they care about is how many stairs you can skate, how to hook up with chicks. But they do hate the internet controls and, of course, terrorism.”

China’s web-censoring Great Firewall, which blocks Facebook, YouTube and Twitter is well known. But the Chinese authorities went many steps further in July 2009 and flicked a switch to turn off Xinjiang’s internet access for ten months after riots between Han and Uyghur residents.

Staying in hotels and even a Kirghiz tent, Terry travelled through Xinjiang, from Urumqi down to the Pamir Mountains, which divide China, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

“I was amazed by the traditional Islamic architecture in Xinjiang. So sick!” he recalls. “It draws you in when you enter the mosque and see the geometric patterns composed by the green glass bricks and yellow and blue ceramic tiles.”

But he could also see Xinjiang was not escaping the rapid modernisation sweeping the rest of China, with ancient Silk Road cities like Kashgar changing forever.

“It is copying the other metropolitan cities – big buildings, skyways, metro, and so on. You are starting to see the old Xinjiang fading: old buildings torn down and old traditions being abandoned,” he says. “Some young people can’t even write in their own language. The municipal authorities were trying to renovate the Old Town into tourism spots. It wasn’t the same any more.”

For Terry, change doesn’t always mean progress. “I really hate to see Xinjiang losing its old flavour while developing.”

You might like

In Medellín’s alleys and side streets, football’s founding spirit shines

Street Spirit — Granted two weeks of unfettered access, photographer Tom Ringsby captures the warmth and DIY essence of the Colombian city’s grassroots street football scene.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Remembering New York’s ’90s gay scene via its vibrant nightclub flyers

Getting In — After coming out in his 20s, David Kennerley became a fixture on the city’s queer scene, while pocketing invites that he picked up along the way. His latest book dives into his rich archive.

Written by: Miss Rosen

On Alexander Skarsgård’s trousers, The Rehearsal, and the importance of weirdos

Freaks and Finances — In the May edition of our monthly culture newsletter, columnist Emma Garland reflects on the Swedish actor’s Cannes look, Nathan Fielder’s wild ambition, and Jafaican.

Written by: Emma Garland

At Belgium’s Horst, electronic music, skate and community collide

More than a festival — With art exhibitions, youth projects and a brand new skatepark, the Vilvoorde-Brussels weekender is demonstrating how music events can have an impact all year round.

Written by: Isaac Muk

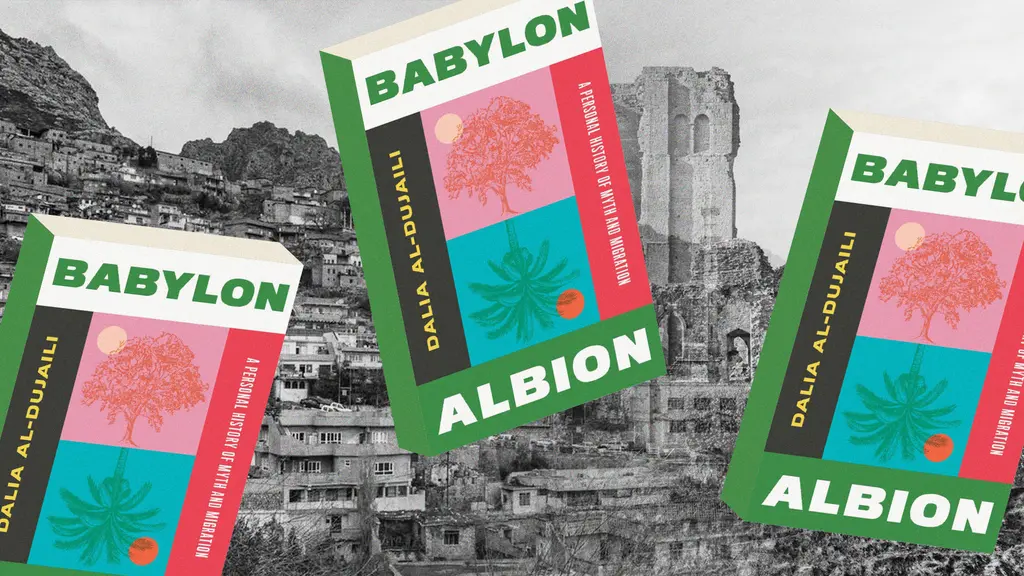

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro