The filmmaker from Damascus finding inspiration in Berlin

- Text by Lara Atallah

- Photography by Lara Atallah

Maps of different European cities hang on the wall dropping hints about Aghyad Abou Koura’s past whereabouts. To the right, a street cone picked up one night and brought back home has been repurposed into a lampshade casting a red-ish light across the room.

It’s night-time in Berlin. The moon is at the waxing gibbous phase, and its light occasionally pierces the cloudy sky, shining through a window next to a framed poster from Nick’s Movie (Lightening Under Water) by Wim Wenders, signed by the director himself.

The documentary chronicles the last days of the life of Nathan Ray, the director of Rebel Without A Cause, who in turn was an influence on Wenders.

And then there’s Aghyad himself. He’s sitting at his desk organising files before beginning one of many long nights of editing his first film. I ask him what the film is about, intrigued by the footage I see.

“It’s about a state of mind,” he says quietly. “It’s not a documentary or a scripted motion picture. It’s experimental, and mostly driven by intuition and unexpected events.”

It’s close to 1am. He lights a cigarette before glancing at the poster. “Nick’s Movie was my entry-point into cinema,” he says. “What I love about it is how the relationship between Wenders and Ray unfolds. It’s one of mutual respect and deep admiration. But to me, it also represents everything that cinema is and should be.”

There’s another reason why Aghyad is drawn to this film. It resembles in more ways than one his relationship to Syrian filmmaker, Ammar Al Beik whom Aghyad met during German language classes two years ago.

The two formed an intellectual bond that eventually led to Aghyad’s interest in cinema. He began learning editing as he watched Ammar work on his films, and from there came the desire to tell his own stories.

My eyes drift back to the maps hanging on the wall, and I can’t help but ask what drew him to collect so many. He says it’s about wanderlust.

“When I first moved here, I relied heavily on maps to lead the way only to realise that cities are always different, and the best way to get to know a place is to get lost in it and let its streets reveal things a map will never tell you about.”

“I can’t visualise Damascus through a map,” he adds. “I know that city inch by inch, and can give you any directions you’d need on the ground. But a map of Damascus makes no sense to me.

“So the maps of the cities that you see here, represent my way of remembering specific trips, certain events that happened, the people I was with, the things that were going through my head at the time.”

Aghyad arrived in Berlin at the end of a long journey in 2015, when Germany announced it would be taking in over 1 million asylum seekers. Having lived a life in Damascus where he was studying to become a dentist, his arrival in a new city – and a new continent – left him with new questions.

Images, and image-making, became the only way to process his new life. Sometimes, it would be a peculiar object that would warrant a photograph: a carriage tipped on its side, sitting on the curb.

His camera has otherwise filmed much less banal moments, such as his face-to-face encounter with Wenders at a signing, or a woman in the park reading out of Robert Bresson’s Notes on the Cinematographer. Ultimately, every frame whether still or moving is a piece of a larger autobiographical puzzle and, as Aghyad sees it, the goal is the pursuit of beauty.

Within that line of thought, Berlin is an endless source of inspiration, and the young filmmaker believes that the energy filling its bustling streets holds all the answers to the questions he’s been asking himself for the past couple of years.

As a photographer, I wanted to spend this time with Aghyad because I was drawn to the way he used his circumstances to radically transform his life and reinvent his narrative as an image maker.

I found myself deeply inspired in his presence as his goals and aspirations brought me back to the time where I first arrived to New York five years ago – having grown up in Lebanon – after deciding to dedicate my life to images.

We’re both trying to make sense of the world through what we produce in places that are alien to us, and it is in that common sense of purpose that I saw in him a kindred spirit.

When I was shooting Aghyad, I began to think in sequences, breaking down images in diptychs, and triptychs, wanting to create a story that echoes his character.

It seemed fitting to include a bird’s eye view of a busy square, Aghyad stopping to photograph, or record something that caught his attention, the nights spent behind a screen replaying a sequence over and over, looking for the exact moment where he should make a cut. In a way, photographing this story became a lot like making a short film with stills.

Pivot Points: Stories of Change from Huck Photographers are shot entirely on the KODAK EKTRA Smartphone.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Largest-Ever Display of UK AIDS Memorial Quilt Opens at Tate Modern

Grief Made Visible — Comprising hundreds of panels made by lovers, friends and chosen family, the UK AIDS Memorial Quilt returns in full for the first time since 1994 – a testament to grief, friendship and the ongoing fight against HIV stigma.

Written by: Ella Glossop

In Medellín’s alleys and side streets, football’s founding spirit shines

Street Spirit — Granted two weeks of unfettered access, photographer Tom Ringsby captures the warmth and DIY essence of the Colombian city’s grassroots street football scene.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Remembering New York’s ’90s gay scene via its vibrant nightclub flyers

Getting In — After coming out in his 20s, David Kennerley became a fixture on the city’s queer scene, while pocketing invites that he picked up along the way. His latest book dives into his rich archive.

Written by: Miss Rosen

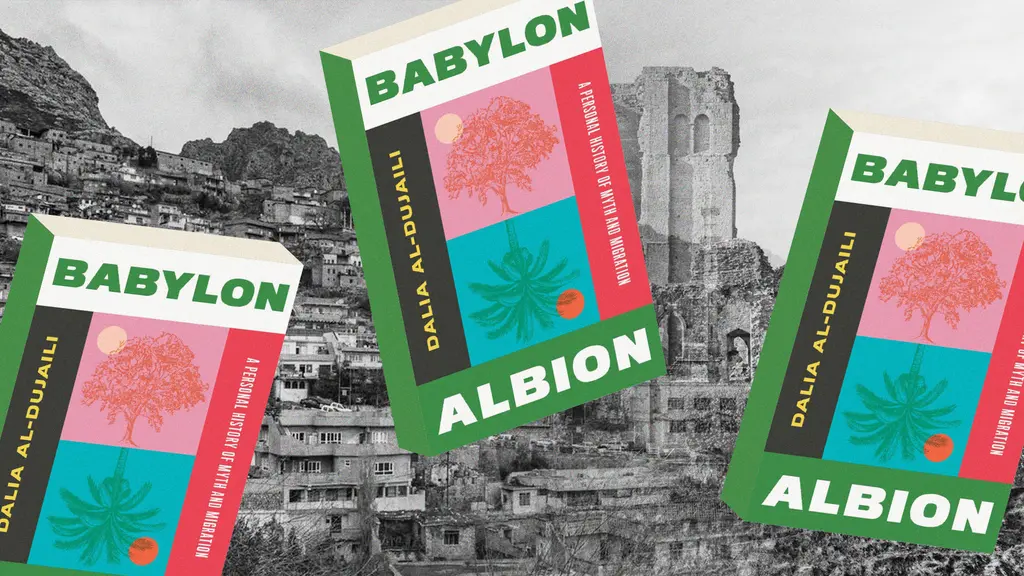

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Why Katy Perry’s space flight was one giant flop for mankind

Galactic girlbossing — In a widely-panned, 11-minute trip to the edge of the earth’s atmosphere, the ‘Women’s World’ singer joined an all-female space crew in an expensive vanity advert for Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin. Newsletter columnist Emma Garland explains its apocalypse indicating signs.

Written by: Emma Garland

We are all Mia Khalifa

How humour, therapy and community help Huck's latest cover star control her narrative.

Written by: Alya Mooro