The beautiful donkeys of Lamu

- Text by Frank L’Opez

- Photography by Frank L’Opez

A version of this story appears in Issue 79 of Huck. Get your copy now, or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Against the clash and wail of God-summoning voices in the sky comes the hee-haw of a lone donkey in anguish. It rises in the swirling island winds that sway the palm trees as if in a restless dream.

An electric moon is beaming violently onto the island of Lamu tonight. It has us by the throat as it zaps straight and low into our eyeballs, hitting the back wall of our skulls and lighting us all up as we float out across the Indian Ocean. “God is great”, the tannoys clamour, firing up one by one from the roofs of all the mosques across the village of Shela. The braying donkey yearns noisily for its mother, protesting bitterly in hunger, crying out that, like the rest of us: it is desperately alone.

For centuries, these working animals have built this East African island and acted as public transport in the continued absence of cars and trucks. They are everywhere, carrying the back-breaking loads of mangrove wood and coral stone in long trains across dunes, white sand beaches and into the maze of narrow alleys.

Mouths make kissing sounds through pursed lips to urge on these sullen-eyed creatures; palms slap their rears to guide the way. When they are not working, like holy cows in India, the donkeys wander freely, scavenging for food and nosing into water holes — working their mouths around jettisoned coconut shells, fruit peels and any detritus worth exploring.

Faiz Abdillah Omar is known on the island as the donkey master. Born in Shela, he is following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather before him. “There is a saying in Swahili that we use,” he says over thick coffee as we sit in the centre of his labyrinthian village.

“If you do not own a donkey, you are a donkey.” Two boys race by on their mounts, their long legs raised to avoid scraping the dusty and uneven ground, sticks striking viciously across grey fur as they sharply urge their rides on in a blur. “If they disappeared from the island, the people would have to work very hard. Many don’t treat them in a nice way — especially in the Old Town.”

Lamu is a Muslim-majority island that forms part of an archipelago off the coast of Kenya. Its Swahili culture and long trading history are entangled in Arabic, Persian, Portuguese, Indian and Chinese influences visible in the architecture, heard in the language and tasted in the food.

To be referred to as a donkey is derogatory or insulting in most cultures but Faiz talks of connection. If he cannot heal them, he is known to bury them:

“I was born with a donkey in the house and have grown with her, but people nowadays just use them like a machine.”

As the bang of hammer on wood grows louder in Shela with Europeans converting derelict Swahili houses into designer homes and the introduction of the boda boda motorbike taxis in the Old Town threatening its UNESCO status, many worry for their way of life. “Donkeys are now rented and then discarded. They are strong enough to carry 150 or 200kg, but if you overload them, beat them and leave them to eat in a dump, that is how you destroy them.”

Faiz is organising Shela’s second-ever Donkey Beauty competition this weekend with the island vet and a local community leader. Donkeys are registered and judged in two categories: ‘Working Donkeys In Best Condition’ and ‘Best-dressed Donkey’. The monetary prize of 15,000 Kenyan Shillings (around £100) is significant enough to get the whole village talking.

Later, I turn a corner to see a donkey with a swollen stomach stagger and fall on its side where children play in the shade. They watch in wonder as she writhes and rolls her eyes, jerking her body away from the ground beneath her. She clambers to her feet as a foal’s head appears in a liquid-filled sack. Mother incredulously faces one way and the foal the other. Ensconced in an opaque helmet, the foal stares blankly as if into outer space, shocked by its own existence as it is thrust out to begin its life along with thousands of others in the dust. Its owner arrives in a sweat, having heard of the sudden news.

“I will call her 2023,” he laughs as its mother licks at the fragility of life itself. Beside her, a viscous lump of placenta attracts flies, turning from pink to purple in the sun.

The following day, I wander to the edge of the village where a soothingly round-cornered mosque looks like it was dropped into the sand. It sits across from the site of Faiz’s clinic. This new project: “A donkey club”, acts as a sanctuary in Shela for those who cannot afford animal feed. It consists of an open pen with a small concrete structure and a deep well. Wooden posts have been wired together to encircle a large herd that stick their faces through the fence, kicking up dust as we arrive. “My phone is always on,” Faiz waves his plastic Nokia at me.

“If someone sees a sick donkey, they know to call me 24⁄7.” With a defunded sanctuary in town and a private vet only open in the week, it has become a vital safe space for beleaguered donkeys pushed to their limits under a blistering sun.

We enter the pen, and buckets of fruit and vegetable peel are soon dumped into wooden troughs. Large handfuls of dried grass are then tossed lightly into a chaos of snapping teeth. “Okay, be careful now,” shouts Faiz as the full force of one fiend knocks me sideways, and black buckets filled with heaps of ground maize render them delirious. Terrifying moans accompany a donkey mêlée around Faiz’s wide grin, “Look how they love it,” he whispers. The morning of the competition is signalled by a chorus of tannoys and cock crowing, like any other morning on Lamu. As the sun rises hard, making it impossible to venture out of the shade, there is the effervescent air of a happening across the village. The slightest interruption to the languid rhythms of Shela becomes monumental to its inhabitants.

Afrobeats thud below an old colonial-looking hotel on the coast, where the village ends, and the vast expanse of flat sands stretch for miles. At around 3pm, riders appear from a distance; the rest drag their animals dressed in garlands of flowers behind them. Those gathered eagerly start whistling and pointing at the surreal parade. Famau Shukri, an imposing community leader in dark shades and a crisp shirt, blows and tuts into a microphone, “testing one, two.”

“We have all gathered for this great competition once again,” he says after loudly clearing his throat over the mic. “We do so to promote kindness in the spirit of Shela itself. Today is for the donkeys to have their day.”

Hamed stands tentatively by the animal he has named Temner; one is as forlorn as the other. “My donkey is too old to win,” he says. “In four years, he will be 23 and won’t work again — not a lot anyway.”

Even with no chance of the grand prize, each entrant will take home 1500 Kenyan Shillings (around £10). Others yank on chains or ropes to constrain their animals that wildly buck and bray their hearts out of fear or the desire to mate. Scuffles and arguments break out that Famau moves in to quell. The competition has ignited the island politics: the feeling is that whatever the decision will be, it will be unfair. Oblivious, red-raw and wrinkled tourists converge to take selfies with anything that moves.

One entrant, Tamza, is patted by her eight-year-old owner, Mariam Seff. The donkey’s hooves, painted in gold, have caught the eye of Miss Lamu in her crown and pageant sash, along with a male model on holiday from Nairobi. With the help of two young schoolgirls, he is to choose the ‘Best Dressed’ donkey. Bedecked with batik of orange and red, Tamza is imperious in golden painted wings made from palm fronds that rest upon her haunches. She must have a chance.

Nawaz Ahmed is 24 and has the swagger of a 70s surfer: all heavy eyelids and sun-bleached ringlets. “This is Blackie,” he tells me. “It is rare to find a black donkey. They are the lucky ones.” Blackie’s fur has been rubbed with coconut oil to make him shine with a luminous and potentially winning sheen.

Two stoic friends dressed in their hotel work uniforms, Japhet Manji and Josphat Safari, are incredibly quiet — their donkey adorned with leftover Christmas tinsel, as calm as the warm waters that lap around their feet.

Faiz arrives with a donkey he washed in the sea at daybreak — scrubbing its hide with salt water for the event. Its colours and ribbons snake excitingly around its wild eyes. “Faiz is more than a donkey whisperer — he is a donkey saint,” Famau tells me. The poker-faced island vet weaves her way through the contestants, taking notes on a pad: “I look at its general condition, searching for wounds. I note its temperament, I check the hooves.” For a person who feeds milk to tiny orphaned kittens, she has the bruising body language of someone not to be messed with.

Men jostle at her intimidatingly. Dr Sharon Masiolo may be a qualified vet, but to some, she is a woman who does not know her place. She handles herself, barely breaking a sweat. “I choose three donkeys for each category, and then it’s down to the children to decide.” The donkey mob swallows up all the space around her.

Faiz’s donkey discards its costume and races away down the beach as Famau takes to the microphone to announce that the finalists from around 30 donkeys will now be called. Jeers and whistles fill the air as three men stand clenching their jaws as two young schoolgirls shyly make their minds up. One touches the nose of a shirking donkey.

“If you do not own a donkey, you are a donkey” See full gallery of the beautiful donkeys of Lamu here

‘The Best Dressed Donkey’ winner is Abu Madi Ali’s ‘Farasi’ — simply dressed in fragile red flowers. “It should be Zam Zam,” shouts one man aggressively. The male model appeases the crowd in Swahili. A donkey erupts in great misery and distress and will not stop.

Famau is back on the microphone again, shoulder to shoulder with the vet. As a master of ceremony, he does not hold back in reminding the crowd of his authority, his voice deep and slow. He holds another envelope with enough money to improve someone’s life for a month.

Yacoub Fun, a furtive teenager in a baseball cap, knows that his donkey, Nushka, could win today. She stands beside him with unblemished ash-grey fur and healthy, curious eyes. The tension among the donkey owners is almost unbearable before a little girl hesitates and then points to Bull, owned by Fayadh Abubakar. Yacoub is as visibly crushed as Fayadh is jubilant. Quickly seizing the envelope, shaking everyone’s hand and then punching the air, he reins in Bull with all his might and screams: “I love my donkey” over the microphone. The other entrants are dismayed that Bull has an ugly brand burnt into its neck — usually, such signs of ownership would make for disqualification, but Bull was a rescue donkey — the cruelty inflicted by another.

“Donkeys are the evil souls reincarnated to suffer for the unspeakable misery they created in another life,” says a man in a grey beard, matter-of-factly. I feel weak from the sun and escape up concrete steps away from the deep sorrow of donkey eyes.

Exhausted, in the Peponi hotel above the beach, I watch the rich residents, oblivious to the struggles below gulp down grapefruit cocktails. I think of pus-filled welts on necks, ankles quivering from the weight of too many bricks, ribs poking through skin trembling at the slightest touch and working until you fall down dead as a reggae version of Bob Dylan’s ‘Knocking On Heaven’s Door’ bumps away to a bloody sunset.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

In Medellín’s alleys and side streets, football’s founding spirit shines

Street Spirit — Granted two weeks of unfettered access, photographer Tom Ringsby captures the warmth and DIY essence of the Colombian city’s grassroots street football scene.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Remembering New York’s ’90s gay scene via its vibrant nightclub flyers

Getting In — After coming out in his 20s, David Kennerley became a fixture on the city’s queer scene, while pocketing invites that he picked up along the way. His latest book dives into his rich archive.

Written by: Miss Rosen

On Alexander Skarsgård’s trousers, The Rehearsal, and the importance of weirdos

Freaks and Finances — In the May edition of our monthly culture newsletter, columnist Emma Garland reflects on the Swedish actor’s Cannes look, Nathan Fielder’s wild ambition, and Jafaican.

Written by: Emma Garland

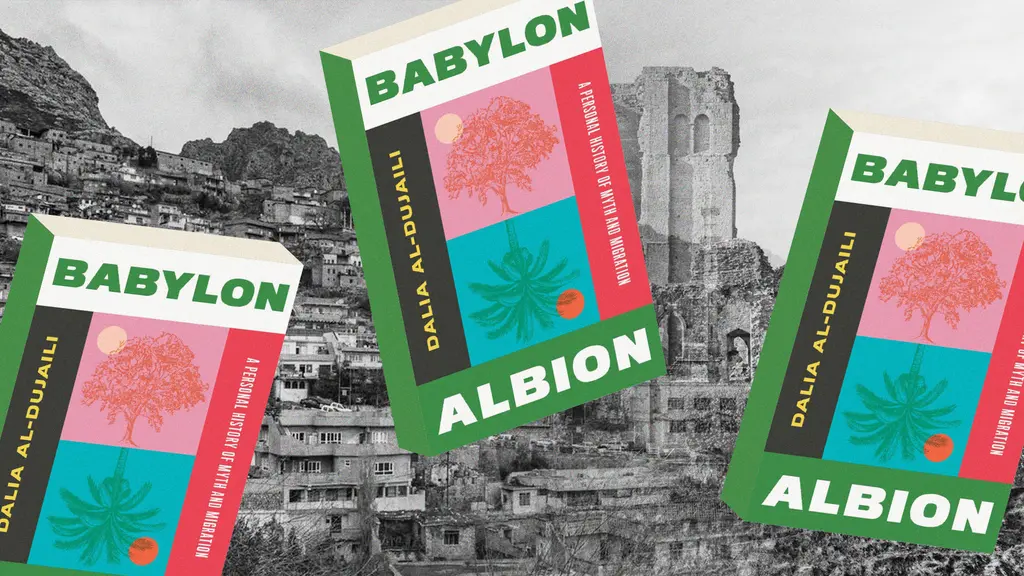

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Why Katy Perry’s space flight was one giant flop for mankind

Galactic girlbossing — In a widely-panned, 11-minute trip to the edge of the earth’s atmosphere, the ‘Women’s World’ singer joined an all-female space crew in an expensive vanity advert for Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin. Newsletter columnist Emma Garland explains its apocalypse indicating signs.

Written by: Emma Garland

Katie Goh: “I want people to engage with the politics of oranges”

Foreign Fruit — In her new book, the Edinburgh-based writer traces her personal history through the citrus fruit’s global spread, from a village in China to Californian groves. Angela Hui caught up with her to find out more.

Written by: Angela Hui