A year on from #EndSARS, and what has changed?

- Text by Conrad Johnson-Omodiagbe

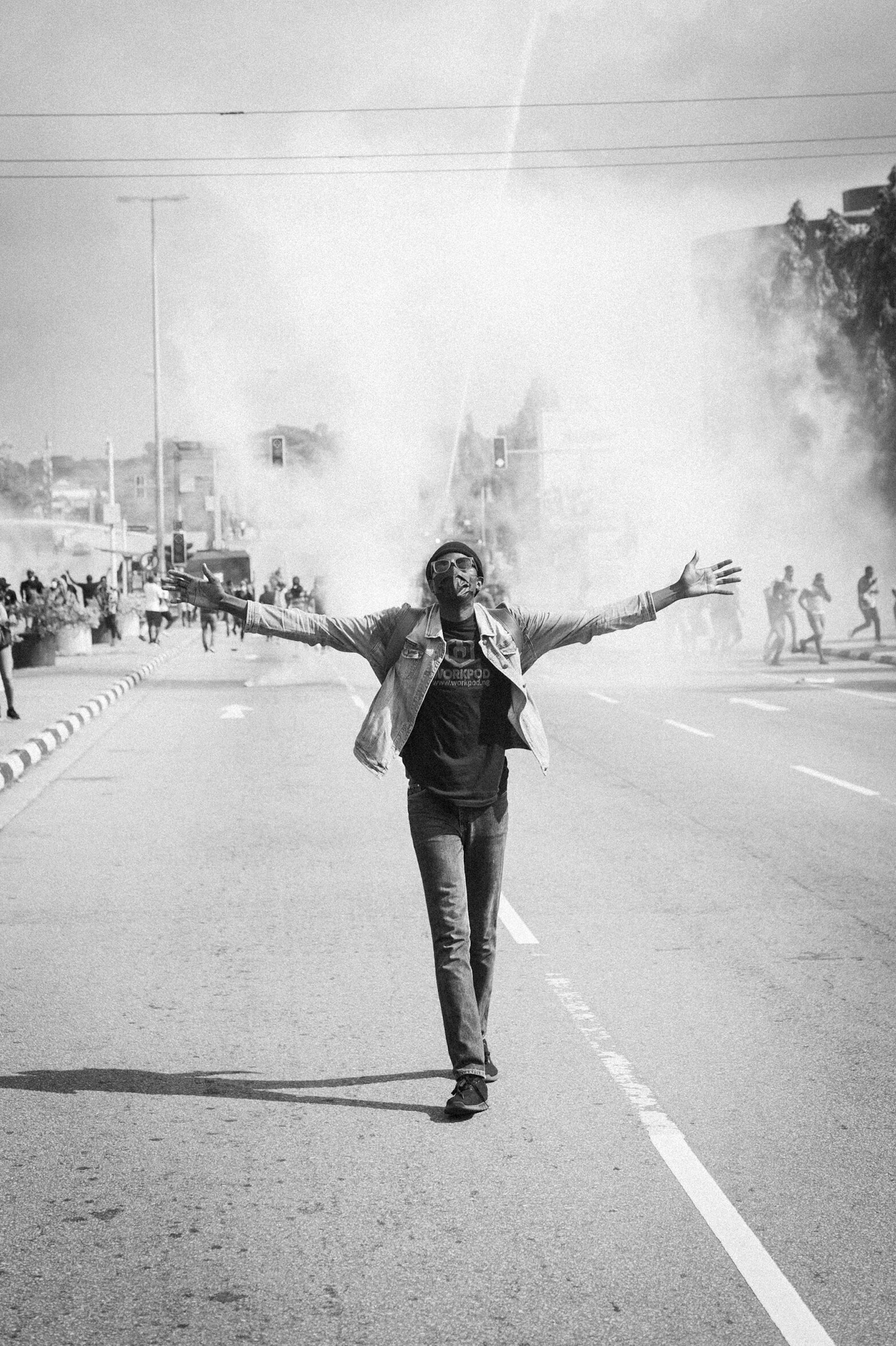

- Photography by Nathan Shaiyen

Adedamola Adeyemi, a fashion stylist, is used to the chaos that is Lagos. Joining other young Nigerians in the country’s popular commercial hub, he navigated these very streets in an impassioned protest demanding an end to the violence committed by law enforcement – particularly, the nefarious Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS). Now, almost a year later, the 31-year-old tells Huck that last month (9 September), he was extorted and harassed by the very people he protested against. How did this happen?

“It started as a regular traffic stop and before I knew it, I was locked up, slapped, and asked to pay N100,000 (£176),” Adeyemi says. He remembers encountering a group of men who identified themselves as officers of the Force Criminal Investigation and Intelligence Department (FCIID), Alagbon, Lagos, at about 10pm on his way back from a shoot. Flashing ID cards and asking for his car papers, Adeyemi says he complied with everything that was asked of him, however, he believes the officers already profiled him as a ‘Yahoo-boy’ (a scammer abusing the trust of internet users), no thanks to his new car, iPhone, and dreadlocks.

Dragging him to one of their stations, Adeyemi didn’t make it home until 3am the next day. “After hitting me, they forced me to unlock my phone and show them my account balance,” he says. Adeyemi also reveals these officers had an Uber driver on standby, who took him to a mobile money agent, where a transfer was processed to facilitate his release. “I basically had to buy my freedom, even though I did nothing wrong.”

Experiences like Adeyemi’s are not isolated events: similar stories have been reported over the past few years, with the pernicious effects of these cases eventually igniting the international movement we’ve come to know as #EndSARS. The movement first began in the early weeks of October 2020, after a deluge of videos showed the shooting of an unidentified young man by a SARS officer.

While this wasn’t the first time Nigerians had seen a video like this, the immobilising effect of lockdown made it easier to focus. This time, the humdrum distractions of a quotidian life couldn’t shake away the realisation that young Nigerians had become prey to the very people sworn to protect them. Swarming the streets, young Nigerians – within and outside the country – blocked major roads and stood outside embassies with one demand: an end to the SARS unit that had become infamous for arbitrary arrests, harassment, torture, and murder, under the guise of fighting crime. With the government failing to take necessary action, the protests eventually morphed into a demand for accountability and better governance.

A year after the protests, questions remain over whether it was a movement resulting in lasting change, or simply a moment. Adewunmi Emoruwa is the Lead Strategist at Gatefield, a public affairs consultancy and media group based in the nation’s capital, Abuja. Speaking to Huck about the effects of the protests, Emoruwa, whose company had its accounts frozen by the Central Bank for supporting the protests, says that while there has been some level of positive change, systemically, this change remains intangible.

“The system hasn’t changed much, it’s still abusive at its core,” he tells Huck. “Although we rarely see them [law enforcement officers] operate in the brazen way they did before the protests, their mode of operation is still crude and with total disregard for human rights. Fear of reprisal has simply made them more covert in their activities.”

But change and accountability are not mutually exclusive. At the height of the protests, Lagos state governor, Babjide Sanwo-Olu, announced a 24-hour curfew that would go into effect in just four hours. With city-wide panic and bumper-to-bumper traffic, thousands of people were forced to rush out of protest grounds, as they struggled to find their way home. However, some protesters decided to defy the curfew and continue their demonstration.

Photographer Roderick Ejuetami (also known as Deeds Art), 28, was one of them. Sitting at the epicentre of the Lagos protests at Lekki Tollgate, hundreds of protesters waved their flags and sang the national anthem with bated breath. What followed was an egregious act: equal parts jarring and heart-wrenching, as videos show the Nigerian military opening fire on peaceful protesters. Amnesty International reported that about 12 people were killed that night, bringing the estimated number of protesters killed during the #EndSARS movement to 56. The tragic climax of what could only be described as one of the most poignant cultural movements in Africa still has young Nigerians in turmoil. “I do not feel like going into that space mentally,” Ejuetami says to Huck. “It was a truly traumatic experience for me.”

Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, the Nigerian government continues to deny that any protesters were killed that night. In a statement made by President Muhammadu Buhari, two days after the protests, the retired military general hammered on international interference in Nigeria’s affairs with no mention of the shootings or the victims. Meanwhile, judicial panels set up across all states to investigate police brutality in the country have been accused of being biased and ineffective.

“All we’ve seen is a rollercoaster of blame with one authority passing the blame to the next. It’s exhausting because even with the judicial panel, no one has been held accountable for what happened that night,” says queer rights activist, Matthew Blaise. Emoruwa expresses a similar sentiment, describing the panel as a “strategic media show designed to make people relax”. After all, this wouldn’t be the first time a panel’s findings had been dismissed by the government – the notable 1999 Oputa Panel, set up to investigate human rights violations during Nigeria’s civil war, also suffered the same fate.

Following the events of October 2020, the Nigerian government announced a ban on the exchange of cryptocurrency – at the time, Nigeria had the world’s second-largest peer-to-peer (P2P) bitcoin market – as well as an indefinite Twitter ban. These actions continue to threaten the fabric of Nigeria’s burgeoning technology sector. Many have viewed these decisions as a direct response to the role these platforms played during the protest, with protesters using Twitter as a tool to organise and cryptocurrency as a major source of funding amidst a clampdown on accounts with traditional banks.

When Kosi*, a 21-year-old Economics student, speaks to Huck, it’s thanks to a Virtual Private Network used to circumvent the Twitter ban. She says that just like Adeyemi, she had been accosted and harassed by law enforcement as recently as October 17, 2021. Held up that Saturday night for almost two hours, she was forced to pay N20,000 (£35) for her freedom. “Things haven’t changed or gotten better. The police seem to be angry that Nigerians dared to protest,” she says. And when asked if anything about the protests could’ve been done differently, Kosi hesitates, eventually telling Huck that, “Challenging the government was in itself, different.”

As Nigerians gear up for the 2023 general elections, Adeyemi is positive that young Nigerians just like himself will turn up en masse to cast their votes and effect change. Emoruwa on the other hand is skeptical. Given that the election process has voters choose from pre-selected candidates supported by money and “godfatherism” at party level, Emoruwa believes we might see an increase in voter apathy.

“We haven’t seen any strong youth movement or organisation that makes us feel like 2023 will be any different and we are less than two years to the elections,” he says. “With the same faces [candidates] popping up again, people might just be disinterested in voting one oppressor over the other.”

Follow Conrad Johnson-Omodiagbe on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.