A country on the edge, captured from within

- Text by Sohrab Hura

- Photography by Sohrab Hura / Magnum Photos

This story appears in The Documentary Photography Special VII. Get your copy now, or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

If I could pinpoint the moment photography became more significant in my life, it would be when my mother was diagnosed with an illness. I was in my last year of high school, and I had also just discovered that my parents had separated. I felt that my whole life had derailed. My father gave me a camera to cope with my mother’s illness and making photographs became a way for me to feel like I existed.

I was born in a small town near Kolkata, India, called Chinsurah. I did my schooling at a boarding school in Dehradun. Growing up, my father was always the family photographer and a really good one too. I am not sure if he knows how beautiful the photographs he took of my mum and I are. Recently, I discovered that he gave me a cheap plastic camera when I was about eight or nine years old. Before that, I had always believed that I started making photographs a little later on in life – because I don’t remember having any interest in photography while growing up.

But years later, when my father gave me that camera following my mother’s diagnosis, it soon became the catharsis I needed. I was able to put a part of me out which seemed to touch people who didn’t know me. It was never a career decision – I still don’t feel like I’m a ‘photographer’ now. Instead, it was always about making this connection with the outside world and feeling anchored by that. Nothing more.

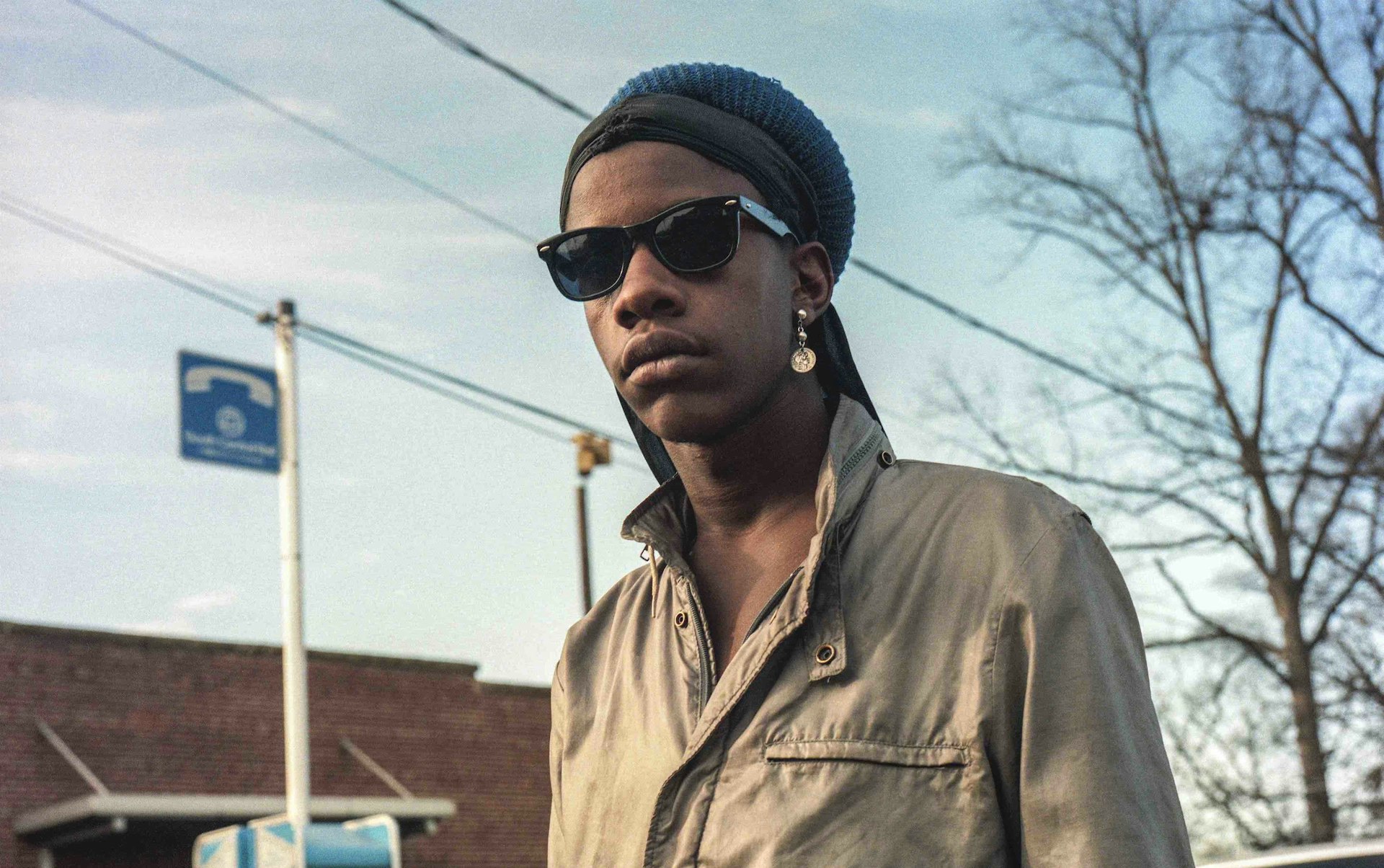

India. 2017. The Village Gateway.

My work, The Coast, comes out of the build-up of an atmosphere of aggression around me in India over many years. That aggression was in the small things: the body language, the gazes I encountered, the tone of voices I’d hear. It was only around six or seven years ago that this aggression took on a more visible form, especially around national elections. I was aware of that discomfort while I was making the photographs, but going back in time over and over again as the work came along made it clearer to me how I needed to shape the work. So instead of a single catalyst affecting the work, it was a series of inflexion points that made the work.

I’ve mixed photographs of both real and decontextualised situations just to push the element of doubt. Doubt is bait I’m using to try and draw the reader into having a second look. The way the world is today, I think having a second look is needed. In that sense, The Coast looks most directly at the system of writing and rewriting narratives. It is about power – because whoever makes these narratives also shapes contemporary and past histories.

I don’t think this is new and I’m also hesitant to wash the work blankly into being about just ‘fake news’, or something like that. I think fake news has always existed, but today it has proliferated many times over. We are also far more aware of this system of generating perspectives through notions of lies and truths. I’m more interested in the working of this system than the lies that it generates. I cannot question the larger system of propaganda without acknowledging my own role in it.

India. 2016. Celebration.

India. 2015. The Butterfly and The Wound.

The undercurrents of the work are somewhat violent in the way I’ve made the photographs because the idea was to reach a kind of pressure-cooker situation where the whistle of the cooker has just started to blow. I feel this is the current state of the region right now – one of anxiety.

In the last few years, there have been many instances of violence – lynchings, riots and other attacks, mostly on people belonging to minority groups. The perpetrators of these acts have responded to rumours fed to them that are conveniently aligned with agendas of supremacy: religion, caste or gender. Fact-checking in the wake of those violent events has often revealed that the images or other information that was spread were deliberately spread out of context.

Take for example Mohammad Akhlaq, a farmworker who in 2015 was lynched to death on rumours that he was eating beef. Later, investigations revealed that the meat in question was in fact mutton. We have come to a point where in order to condemn the murder of a man we have to first identify the food that he had eaten. In my work maybe an image is violent in one context, maybe innocuously funny in another. By not letting anyone meaning settle onto the images, I hope the reader thinks more about the larger context – and not just the images themselves.

India. 2018. The Joke.

India. 2016. After the fight.

India. 2014.

India. 2015. Sana getting ready to go out.

This story appears in The Documentary Photography Special VII. Get your copy now, or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

The Coast is published by Ugly Dog.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.