The artist making his entire digital footprint public for us all to see

- Text by Mark Farid

- Photography by Mark Farid

We are regularly told that if we do not agree to the terms and conditions of a service online, we have the choice not to use it. ITunes? Gmail? Facebook? They pretty much all say the same. Life is much simpler when we just click “yes”, and agree to whatever they ask for, but I wanted to try refusing.

So, I attempted to excerpt my right to disagree for six long months. We may be told there’s a choice when it comes to agreeing to whatever small print we find attached to these services, but turns out the alternative leads to an isolated, often culturally desolate and financially debilitating existence. It got me thinking about how and why we live out our lives online, and what we truly understand about the data we share.

It led to my last exhibition, Data Shadow, which took place inside an 8x2m blue shipping container in central Cambridge. It was an individual experience, inviting in one participant at a time, lasting just two minutes or so. Upon entering the container, you were asked to sign a contract and join our WiFi.

At this point, we took the final 1000 characters of the participant’s most recent text messages, and 64 images from their phone’s camera. In the second half of the container we inserted there text messages and images into separate digital shapes of the participant in realtime.

To culminate the project in October 2015, at a talk titled ‘Anonymity is our only right, and this is why it must be destroyed’ at the University of Cambridge. I gave away the passwords to my entire digital life during the event. From my Facebook and Twitter accounts to my personal and work email addresses, my Apple ID and everything in between, I offered up my details to the audience, which included my (closed) online banking details.

I wanted to delete my digital footprint, but since we do not own our own digital footprints, the only way I could think to delete them was to give away all of my login details.

This meant when people changed the passwords, I could no longer access my accounts. More than this though, with other people logging into my accounts and doing whatever they wished, the data companies had on me, ‘Mark Farid’, would no longer truly be mine.

From 26 October 2015 until 30 April 2016 I tried to live without a digital footprint. For the first 6 weeks I had no phone or computer. At first it was incredibly liberating, freeing one might say. I became more engaged in everything, I remembered what boredom felt like, and when it came to making arrangements with family and friends, both parties were forced to stick to plans and be on time.

As time went on it became increasingly hard to make arrangements, organising my work was impossible. But, I still wanted to avoid being tracked.So I got multiple laptops which I used for different things, in different locations, whilst also using VPNs that would tell prying eyes that I was in different locations. I paid using cash for everything, and replaced my phone and sim-card every month.

After the 6 months were over, I was so excited to use technology in a conventional, convenient way again. I can’t emphasise enough looking back just how distressing a period those six months became. Leading a normal life was impossible, and it dawned on me that we really do not have a choice when it comes to using computers and phones, the services and platforms, and ultimately the terms and conditions that they dictate. And that’s before we consider the role the state can play in keeping tabs on us day to day.

Mark’s physical digital footprint

Treading the line between security, business practice and civil liberties is a very delicate balancing act, but our rights to privacy and to anonymity should not be forgotten. Thinking “I have nothing to hide so why worry” is based on the presumption that we are guilty until proven innocent. It puts us on the defensive, and unless you conform you are seen to be guilty.

As technology continues to further intrude into our private spaces, and our approach to privacy and protecting personal data continues to loosen and become normalised, I find it extremely difficult to believe that something fundamental will not change in the human psyche.

Currently we do not own our digital footprint, nor do we know who has copies of what information, and who owns the different parts. Our entire digital life is being potentially monitored at any given time, by anyone. Granted, in 2016 this hasn’t caused any measurable impact to many individuals that we know of, but it’s only a matter of time.

My next project, Poisonous Antidote, will see me broadcast all of my personal and professional emails, text messages, phone calls, Skype, Twitter, Instagram and Facebook chats to the public. Everything will be publicly streamed in real-time, along with all Facebook tags, uploads, locations, web browsing, app use and music shared live online.

At Gazelli Art House in London, an algorithm written by designer Vicente Gasco will take each days worth of data, and print it in 3D inside the gallery space. Each day’s print connects to that of the previous day to create my own personal, physical digital landscape.

By publicising the 24-hour accessibility of my own digital life in this way, I’m interested to see what happens when privacy is visibly removed.

When privacy no longer exists, how will I react? In the knowledge that my every act will be broadcast for all to see, will I be able to hide the facets of my life and character that refuse to fit into political, social and cultural norms? The thought processes behind my actions: my desires and my desire to be judged by those watching me will become inextricably intertwined, I’d assume.

It’s a sign of what’s to come when everything is shared for anyone, leaving privacy, and in turn individuality to become eroded in exchange for a homogenised and globalised cultural identity.

Poisonous Antidote will run from 1 September – 1 October 2016 at Gazelli Art House in London. Keep track of the project on the website too.

You might like

Capturing life in the shadows of Canada’s largest oil refinery

The Cloud Factory — Growing up on the fringes of Saint John, New Brunswick, the Irving Oil Refinery was ever present for photographer Chris Donovan. His new photobook explores its lingering impacts on the city’s landscape and people.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Susan Meiselas captured Nicaragua’s revolution in stark, powerful detail

Nicaragua: June 1978-1979 — With a new edition of her seminal photobook, the Magnum photographer reflects on her role in shaping the resistance’s visual language, and the state of US-Nicaraguan relations nearly five decades later.

Written by: Miss Rosen

A visual trip through 100 years of New York’s LGBTQ+ spaces

Queer Happened Here — A new book from historian and writer Marc Zinaman maps scores of Manhattan’s queer venues and informal meeting places, documenting the city’s long LGBTQ+ history in the process.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Nostalgic photos of everyday life in ’70s San Francisco

A Fearless Eye — Having moved to the Bay Area in 1969, Barbara Ramos spent days wandering its streets, photographing its landscape and characters. In the process she captured a city in flux, as its burgeoning countercultural youth movement crossed with longtime residents.

Written by: Miss Rosen

In photos: 14 years of artist Love Bailey’s life and transition

Dancing on the Fault Line — Photographer Nick Haymes’s new book explores a decade-plus friendship with the Californian artist and activist, drawing intimate scenes from thousands of pictures.

Written by: Miss Rosen

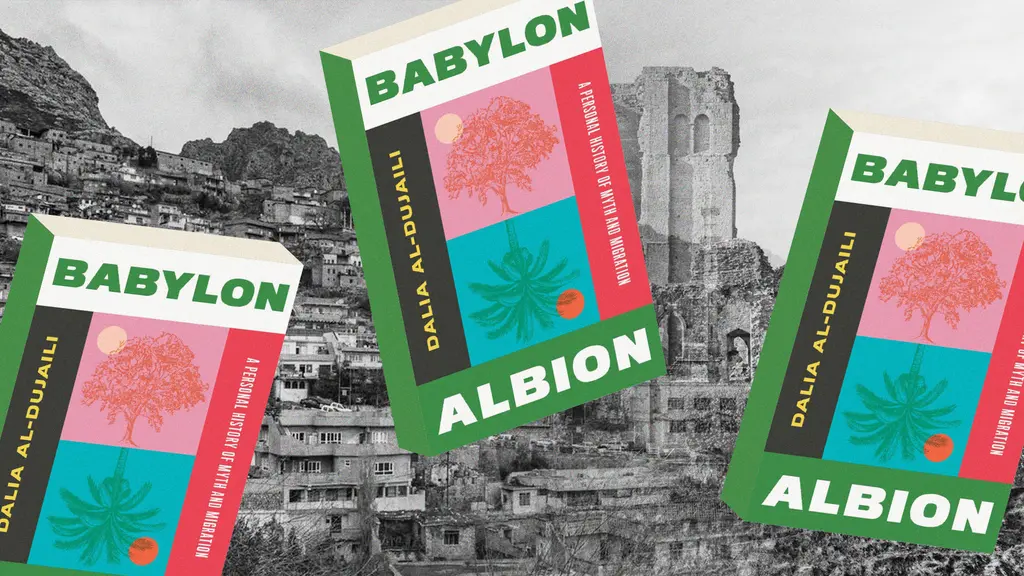

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori