How unions could transform work under capitalism

- Text by Katie Goh

- Illustrations by Make Bosses Pay: Why We Need Unions, cover art courtesy Pluto Books

No matter what any Tory politician says, there’s still power to be had in a union. This is the central thesis to political journalist Eve Livingston’s new book, Make Bosses Pay: Why We Need Unions (Pluto Books), a manifesto for the power of collective action in the workforce. Despite unions often portrayed as dwindling relics of the past, in her book, Livingston points out that many of today’s dissatisfactions with capitalist work – equal pay, burnout, precarious gig-economy positions, sexual harassment in the workplace – could be tackled by the collective front of the union.

“Unions are the best tools or vehicles ordinary people have for achieving any kind of social justice or tackling any kind of inequality,” Livingston explains. “They’re a mechanism for moving the dial in society at large. It might seem like unions are a niche topic, but I actually think they’re central to the conversations we’re having about equality and social justice and how we want society to look like.”

Ahead of the release of Make Bosses Pay, Huck spoke to Livingston about how unions have changed in the last forty years, collective action versus individualistic workplace solutions and why HR is definitely not your friend.

In Make Bosses Pay, you outline the history of the union which has changed as the nature of our work has changed. What kind of changes have there been to unions more recently?

One of the central arguments of the book is the idea that when people think of a union, they often think of a sort of entity that’s separate from them, like, a building or a picket line or a branded tote bag. What I try to do in the book is instead define a union as a commitment between people. That’s not necessarily something that’s changed – I think that’s always been what a union has been, or at least how we should understand a union.

But what springs to mind when I’m thinking about how the union, as an entity, has changed, or is changing, is the evolution of the model they were built on. When unions were first built, they were built on the model of a white male breadwinner: men going off to work in manual industries and earning enough money to look after their whole family. That’s a generalisation, of course, because there have always been working-class women who have worked, but certainly unions were built on that understanding that collective bargaining was to secure men a family wage. I think unions have long recognised that that can’t be the model anymore – but I think they’re still in a state of transition to something that encompasses more liberatory politics.

The issues you raise in the book encompass every generation, but you focus particularly on young people in relation to unions. Why was that?

Like you say, there’s no line between generations; these issues cut across different generations and there are older people who are in precarious work and renting, the same as younger people. But I suppose the reason I focused on young people was that there is a preoccupation in the public conversation that when we do talk about unions, it’s always about this crisis of their existence. Like are they going to exist in 10 or 20 years? And when you look at the membership numbers, young people haven’t been joining in the same numbers since the heyday of the ‘70s.

There is this existential crisis about young people not having a relationship to trade unionism. And they’re the people who need to be recruited if unions are going to survive. So that’s the central reason I focused on young people. And I also think a lot of young people are very politically engaged and doing great queer organising, migrant organising, feminist solidarity movements and anti-cuts movements. We need to build a trade unionism where that sort of political work can be union work.

Why do you think young people don’t have a relationship to trade unionism?

We can’t ignore how beaten down unions have been since the ‘80s. They’ve had so much of their power removed and are so restricted in the conditions in which they can operate. That creates the perception of them as weak and toothless. I’ve heard people say, “I would join the union at my work but it’s rubbish, it doesn’t do anything.” There’s that perception which isn’t entirely the union’s own fault – it comes from the difficult contexts they’re operating in.

But I do think the labour market itself has changed quite dramatically within that time frame: unions were built on this manual labour model of men working physically on dockyards and mines and that’s just not the case anymore. We’ve transitioned from a productivity economy to a service one, where people are working in hospitality, retail, care, those kinds of jobs. And unions just aren’t in those workplaces in a lot of cases. So if you’re a young person having a hard time at work and you start looking for answers, your union isn’t there as an obvious place for you to turn.

There’s a chapter in the book dedicated to the role of HR and how we’ve come to see it as a replacement for unions. How has that happened?

We have it in our heads that HR is there for us; they’re your champions in the workplace. But when you start to think about what their actual role is, it’s not even hidden, it’s on the surface – their name is ‘Human Resources’ – so it’s about you, as a resource, for the organisation you’re working for. HR exists to utilise workers in a way that meets the organisations’ strategic aims. To me, that’s always going to be in conflict with the interests of workers.

Obviously the shape of that differs in different workplaces, but that’s the core dynamic that’s in play in a capitalist society. And so, HR will look out for you in so far that it wants you to be productive, so they might give you some good equipment or let you do compression hours so you’re more satisfied and less likely to complain, but they’re certainly not going to fight for pay increases or a four day working week if it’s going to adversely affect the organisation’s ability to meet its aims. They’re just not an answer to an independent union.

The role of HR as solving individualistic issues and not collective workforce issues seems to sum up the nature of work right now. We look at issues like burnout as individual’s problems, not structural workforce problems which unions can play a role in tackling.

There is a huge conversation happening around work and young people’s dissatisfaction around capitalist work. You see things like burnout in headlines, and issues like the Me Too scandal which was, at its core, about working conditions and women facing sexual harassment in the workplace. We saw the BBC have a huge equal pay scandal.

People were concerned about these issues and articles popped up in the aftermath saying things like, ‘Here’s what you can do if you get sexually harassed at work or if you’re being paid less than your male counterparts’ – but those articles never mention unions. They talk about mindfulness or sending a polite email to HR or booking a meeting with your boss but that’s just not relatable to me and the workplaces I’ve worked in. That’s not the type of workplace most people are in. It struck me that there is a conversation around young people’s dissatisfaction with capitalist work, but the answers they’re sold are so individual.

So you get books about how to cope at work and be productive and Instagram influencers posting graphics about how to negotiate with your boss, but they never talk about trade unions or collective action. To me, collective action is the only counter to the power of your boss and capitalist work.

Where do you see the future of the union going?

I really hope to see a focus on organising and giving people a political education, talking to them about capitalism and the exploitation of workers and why the issues they’re facing are collective and not individual, building new trade unionists who stick around for a long time. I’d like to see them do that work rather than servicing members with ad-hoc bits of advice and discounts.

I think there are reasons to be optimistic, not just in terms of the union increase we’ve seen during the pandemic, but also because there are these great case studies of the existing union movements doing this work already. If you believe it’s powerful for people to come together and make a commitment to each other and speak as one voice, you can’t really be pessimistic – it’s just a big challenge! But if the work gets done, the potential is huge.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Make Bosses Pay: Why We Need Unions is released by Pluto Books on 20 September.

Follow Katie Goh on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

A reading of the names of children killed in Gaza lasts over 18 hours

Choose Love — The vigil was held outside of the UK’s Houses of Parliament, with the likes of Steve Coogan, Chris O’Dowd, Nadhia Sawalha and Misan Harriman taking part.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Youth violence’s rise is deeply concerning, but mass hysteria doesn’t help

Safe — On Knife Crime Awareness Week, writer, podcaster and youth worker Ciaran Thapar reflects on the presence of violent content online, growing awareness about the need for action, and the two decades since Saul Dibb’s Bullet Boy.

Written by: Ciaran Thapar

A visual trip through 100 years of New York’s LGBTQ+ spaces

Queer Happened Here — A new book from historian and writer Marc Zinaman maps scores of Manhattan’s queer venues and informal meeting places, documenting the city’s long LGBTQ+ history in the process.

Written by: Isaac Muk

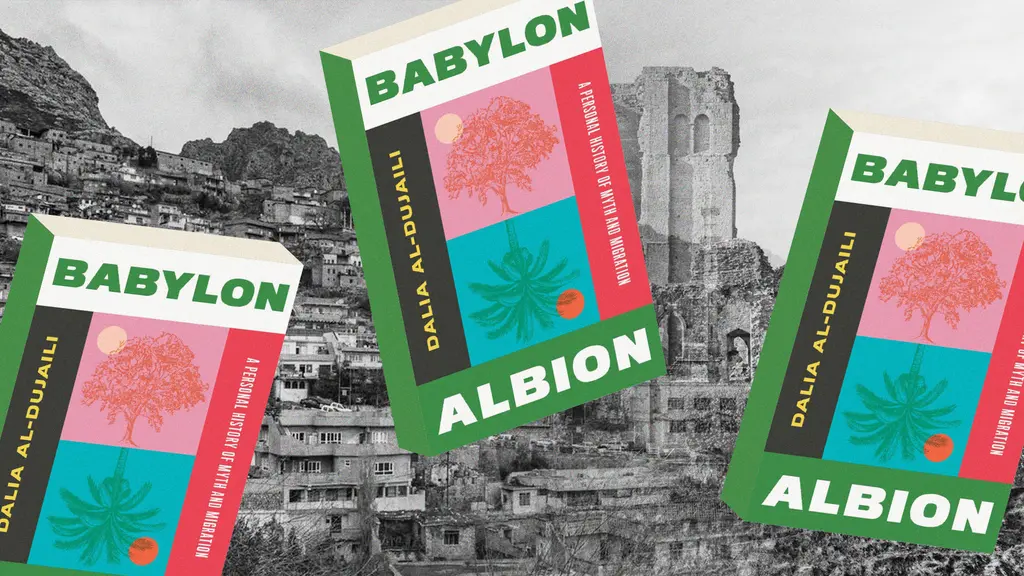

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Meet the trans-led hairdressers providing London with gender-affirming trims

Open Out — Since being founded in 2011, the Hoxton salon has become a crucial space the city’s LGBTQ+ community. Hannah Bentley caught up with co-founder Greygory Vass to hear about its growth, breaking down barbering binaries, and the recent Supreme Court ruling.

Written by: Hannah Bentley

Jack Johnson

Letting It All Out — Jack Johnson’s latest record, Sleep Through The Static, is more powerful and thought provoking than his entire back catalogue put together. At its core, two themes stand out: war and the environment. HUCK pays a visit to Jack’s solar-powered Casa Verde, in Los Angeles, to speak about his new album, climate change, politics, family and the beauty of doing things your own way.

Written by: Tim Donnelly