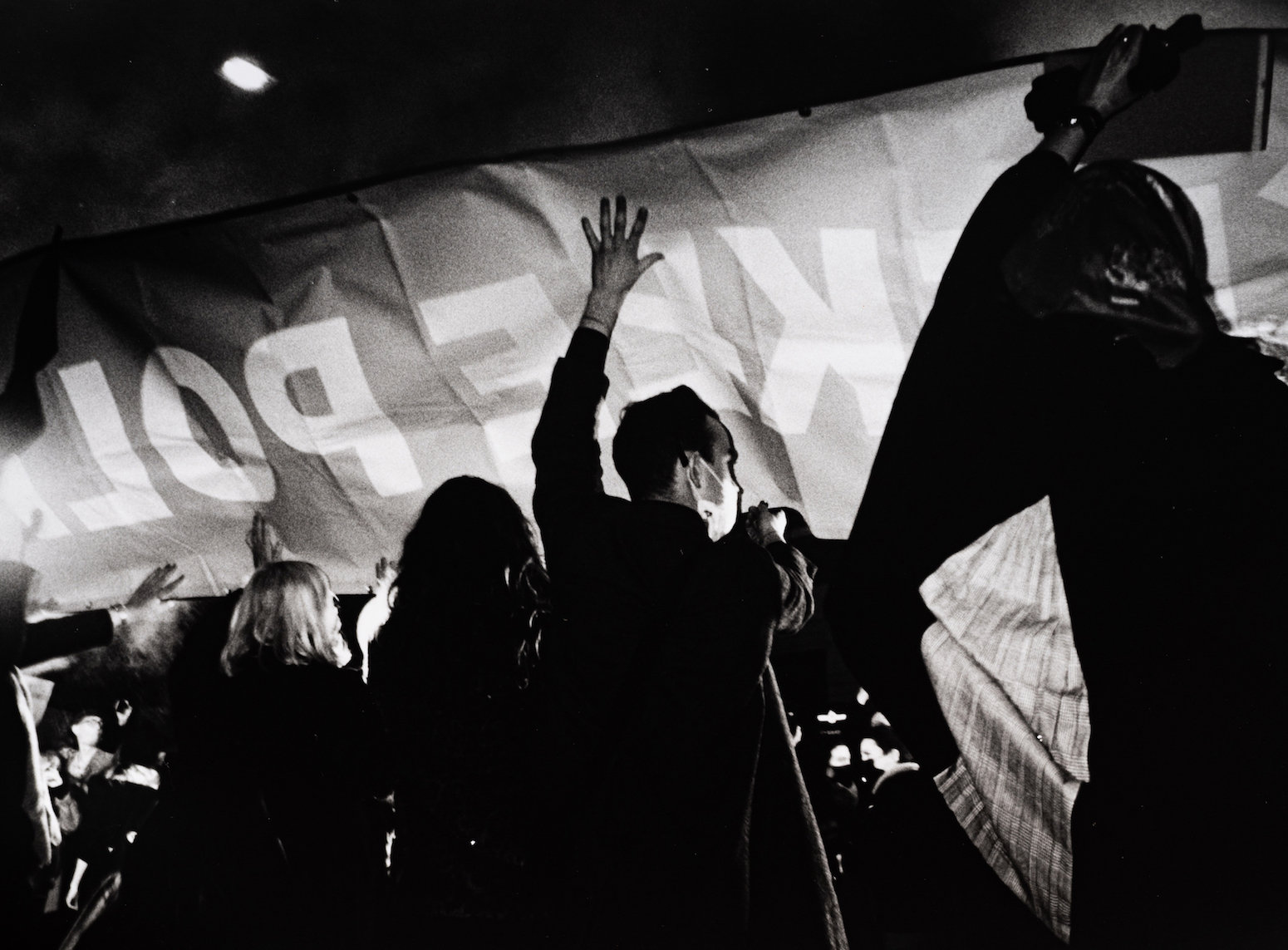

Inside the fight against Poland's abortion ban

- Text by Alexander Durie

- Photography by Piotr Bułhak

Justyna Wydrzyńska’s phone has been going off non-stop this year. Before October, it was already ringing more than 15 times a day. On the weekend of October 24th, it was around 300 times.

In late October, the largest protests in Poland’s modern history began in the Polish capital after the right-wing populist government, the Law and Justice Party, tried to impose a near-total abortion ban. Initially, Wydrzyńska couldn’t join because she lives in the small town of Przasnysz, around 100 kilometres north of Warsaw.

But it turned out that the bigger the protests were getting, the more calls she was receiving on the helpline number of Abortion Without Borders (AWB) – the organisation she helped found. The initiative, which was launched in December 2019 by activist groups in Poland, the UK, Germany and the Netherlands, aims to help anyone in Poland who contacts them seeking a safe and legal abortion in Poland or abroad through various abortion support groups.

A year later, AWB has faced the challenges of a global pandemic – which has made accessing safe abortions in Poland or abroad even more difficult – and a Polish government deeply tied to the Catholic Church that is trying to further suppress reproductive rights.

“We are filling the gap our government should fill,” Wydrzyńska says. In this turbulent year, the need for a movement defending people’s rights to safe abortion has become all the more acute.

In 2020, Poland is one of the few EU countries left with highly restrictive abortion laws. It is only permissible in cases of rape, incest, a mother’s life being in danger, or severe fetal abnormality. On 22 October, Poland’s tribunal court ruled that abortion due to fetal defects was unconstitutional. Mass protests erupted and pushed the government to delay the implementation of this new law to an undefined date.

Many believe that one of the main reasons for the ruling party’s rebukes on minority groups and reproductive rights is due to its long-standing association with the Catholic Church. Author and journalist Karolina Lewestam, who is from Warsaw, explains how the Church had a role of “liberator” following the fall of communism and implemented nationalist values in Polish identity. But a generation later, this thinking is starting to shift.

“One of the things that makes these protests different is that many people who are protesting are very young,” Lewestam says. “There is a taboo that has been broken, somehow, and I don’t think that anyone has realised – including the governing party – that there is a huge amount of people who just don’t really care about the role of the Church.”

According to a 2018 study by the Pew Research Centre, Poland is the country with the biggest generational decline in religiosity among the countries surveyed. Despite more than 90 per cent of Poles declaring themselves to be Catholic, only 16 per cent of adults under 40 say that religion is very important to them.

According to Lewestam, the new generation that is protesting is not only less influenced by the Church, but more digitally connected and quick to mobilise. She says the Polish government tried to use the pandemic as an opportunity to implement the new restrictions on abortion, but to no avail.

Easier access to information for young people has meant that the popularity of groups like AWB has grown tremendously. Much of the reason AWB is becoming known across Poland is thanks to Abortion Dream Team, which takes care of publicising the work done by activists through social media campaigns, stickers and slogans chanted in protests. Katarzyna Korytowska, a protester in Warsaw, says that the helpline number is sprayed on walls across the city and chanted in protests.

“More people know that there is this helpline and that they can get relevant, trustworthy, comprehensive information about their options, so they call because they trust us,” says Karolina Więckiewicz, a lawyer and the founder of Abortion Dream Team. “But there are also people who are calling us only because they are afraid of what this decision might change, and what it might mean for them in the future.”

Więckiewicz says that “99 per cent” of the calls AWB receives are regarding pharmacological abortions. This abortion method, also known as a “home abortion”, can be used safely by taking pills – mainly misoprostol – until the 12th week of pregnancy. It is completely legal in Poland, as long as it is managed by the pregnant person themselves. Though pills are not sold by doctors or hospitals, they are legally purchased from abroad by AWB, who make them available to those seeking early abortions across Poland.

“Giving information is not a crime,” Więckiewicz says. “There were a lot of misconceptions but also not enough knowledge about medical abortion with pills.”

In her campaigning work travelling around Poland, Więckiewicz has found that it isn’t abortion that’s the problem, rather, it’s the stigma around it. “Abortion is perceived as something bad, something immoral, something to limit,” she says.

For those who cannot perform a “home abortion”, their best option is to have an abortion abroad. On November 22, a month after the Polish court ruling, Abortion Dream Team posted on Facebook that it has helped 61 people travel abroad – three times more than in a typical month.

Emilia*, a 30-year-old software developer from Warsaw, is among those who’ve recently benefitted from this support. She’d already had five abortions in the last ten years and managed to terminate them herself by acquiring cheap misoprostol pills “from sketchy classified ads”. But earlier this year, she got pregnant again, and after a few months, she discovered that the pills hadn’t worked. Her only choice was to have an abortion abroad.

“I already googled everything for an abortion in the Netherlands, but decided to call AWB just to be guided by a friendly voice. I think any woman in such a situation would appreciate that,” Emilia says.

“I call myself lucky,” she continues. “I think it’s also a class issue: it’s hard to get access to an abortion without basic digital literacy and some material resources.”

Although Polish abortion rights activists have been active for several years, the central role of the initiative is providing financial support.

“What we were missing at some point was to financially support those who want to travel to other countries because it’s been going on forever now,” Więckiewicz explains. “Traveling for abortion to other countries is the second most commonly chosen option. But people have to have money.”

The main organisation that oversees the financial running of AWB is the UK-based Abortion Support Network. Founded in 2009, it’s the first abortion fund in Europe and held a crucial role in helping people from Northern Ireland obtain abortions in England.

Founder Mara Clarke recognised that class plays a huge role in who can access an abortion. The charity gives money to those in need of support following a “very frank conversation” about their financial means, without asking questions on their reason for wanting an abortion.

Abortion Support Network has expanded significantly beyond what Clarke describes as its “five volunteers with a bucket of change” it started off with. The group, funded by 1,100 donors, received an extra £30,000 from donors after 22 October.

“We are very, very creative problem solvers,” Clarke says of the obstacles her and other members of the group faced this year, in which many seeking abortions couldn’t move, hospitals abroad were often not taking international clients or were prioritising those with coronavirus.

Zuzanna Dziuban, a 39-year-old member of AWB in Berlin for the activist group Cicia Basia, expresses similar feelings. “Before the pandemic, we would have three, four people a week coming to have procedures, and several dozen deciding to order pills. During the pandemic, we’ve had weeks where we had eight, nine, even ten people coming,” Dziuban says.

The nature of the pandemic meant that Dziuban and other activists also had to adapt to unusual circumstances. During the height of the pandemic, for example, there was more demand for private accommodation than hotels. “We almost felt like an abortion travel agency,” Dziuban says.

Dziuban has also found many emotional challenges in her work with Cicia Basia, such as telling someone that it’s too late to get an abortion. “This is the most disturbing moment in activism,” she says.

Poland still has a long way to go until abortion is decriminalised and that political power changes sides. But the ongoing protests across the country and the work done by AWB have reminded those in Poland seeking abortions – or merely information – that they are not alone.

After 16 years of activism, Wydrzyńska looks back with pride at the work her group has achieved. “In the beginning, we felt that we were alone and that were just a few of us activists,” she says. “Now there are so many people on the streets, and they are screaming: ‘I can feel. I can decide.’”

*Name has been changed to protect identity

Find out how to support Abortion Without Borders by visiting their official website.

Follow Alexander Durie on Twitter.

Follow Piotr Bułhak on Instagram.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Meet the Kumeyaay, the indigenous peoples split by the US-Mexico border wall

A growing divide — In northwestern Mexico and parts of Arizona and California, the communities have faced isolation and economic struggles as physical barriers have risen in their ancestral lands. Now, elders are fighting to preserve their language and culture.

Written by: Alicia Fàbregas

A new book explores Tupac’s revolutionary politics and activism

Words For My Comrades — Penned by Dean Van Nguyen, the cultural history encompasses interviews with those who knew the rapper well, while exploring his parents’ anti-capitalist influence.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Youth violence’s rise is deeply concerning, but mass hysteria doesn’t help

Safe — On Knife Crime Awareness Week, writer, podcaster and youth worker Ciaran Thapar reflects on the presence of violent content online, growing awareness about the need for action, and the two decades since Saul Dibb’s Bullet Boy.

Written by: Ciaran Thapar

The UK is now second-worst country for LGBTQ+ rights in western Europe

Rainbow regression — It’s according to new rankings in the 2025 Rainbow Europe Map and Index, which saw the country plummet to 45th out of 49 surveyed nations for laws relating to the recognition of gender identity.

Written by: Ella Glossop

Meet the trans-led hairdressers providing London with gender-affirming trims

Open Out — Since being founded in 2011, the Hoxton salon has become a crucial space the city’s LGBTQ+ community. Hannah Bentley caught up with co-founder Greygory Vass to hear about its growth, breaking down barbering binaries, and the recent Supreme Court ruling.

Written by: Hannah Bentley

Jack Johnson

Letting It All Out — Jack Johnson’s latest record, Sleep Through The Static, is more powerful and thought provoking than his entire back catalogue put together. At its core, two themes stand out: war and the environment. HUCK pays a visit to Jack’s solar-powered Casa Verde, in Los Angeles, to speak about his new album, climate change, politics, family and the beauty of doing things your own way.

Written by: Tim Donnelly