Terence Nance is the mind-bending misfit film needs now

- Text by Simran Hans

- Photography by Alex Ashe (main image)

Terence Nance is eating a late lunch – something with cashew cheese from a nearby vegan spot – as he reflects on the tight-knit upbringing that shaped him. The 36-year-old filmmaker is speaking over the phone from his home in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant, with a soft Texan drawl that feels both warm and familiar.

The second of four children – two brothers and a younger sister – Terence describes himself as the odd one out. “My mother told me that growing up, all six of us would walk into a room and if my parents and siblings would walk to the right, I would walk to the left,” he remembers. “I was a little to myself. Not private, but kind of off in my own world.”

Terence’s wry, introspective debut An Oversimplification of Her Beauty (2012) sketched out his inner world in the wake of a break-up, playfully illustrating his spiralling thoughts with trippy animated sequences and documentary-style inserts. Since then, he’s directed and produced several short films, recorded music with his band Terence Etc., as well as created an acclaimed TV series for HBO (Random Acts of Flyness).

Next up, he’ll direct Space Jam 2, produced by Black Panther’s Ryan Coogler and starring LeBron James, a project he describes as “a little more complicated than the words ‘sequel’ or ‘remake’ are able to communicate”.

Terence is a man of many mediums, a multimedia artist in the true sense of the word. It started when he studied visual art (not filmmaking) at Northeastern University in Boston and NYU in New York, before zipping to Paris after grad school to complete an artist’s residency. Although he gravitated back to Brooklyn in 2010, he still sees being raised in Dallas as an important part of his identity.

“In the ’80s and ’90s, being isolated really meant being isolated,” he says with a chuckle. “There wasn’t access to another cultural way to be. When my cousins would come out from the Bay Area, what they were listening to would be totally different. Just growing up in the cultural soup of Dallas, in the black community – I can see who I am because of that.”

From Random Acts of Flyness, courtesy of HBO.

Still, he’s not entirely comfortable calling New York City home, admitting to a sense of envy for anyone who truly identifies with a particular geographical place. Maybe New York will feel like ‘home’ at some point, he says; maybe he’s just not that sort of person… or maybe New York just isn’t that sort of place.

“I’m finding, especially for artists, it’s cost-prohibitive,” says Terence, his voice changing. “You see your communities becoming segregated along race and class lines because people can’t afford to live there any more. It makes it like, ‘Why don’t I just move to Cincinnati?’ It becomes less… sustainable, like spiritually and socially, to stick around. And with other shit, like initiatives and non-profit work, all kinds of stuff happens when people are just together and talking. But you can’t be together and talking if you can’t pay the rent.”

What does sustain Terence is something he calls “The Swarm”. By his own admission, it’s “a crude demographic thing” he came up with to better discuss “the black or black-adjacent people who find themselves in fractal, interlocking social networks in different cities”.

Swarm Theory draws a distinction between The Swarm (creatives like Terence), Industry (“the people who work at MTV or BET or Def Jam – they’re like sneakerheads who live in Manhattan”), and Buppies (black yuppies, “people who went to Ivy League schools and got jobs in banking or consulting”). The way he describes it sounds less like an exclusive club than it does the treatment for a TV show.

“The Swarm is people like me who expatriated – they mostly live in New York or LA. They get jobs like teachers, artists or work in non-profits, or else they are in grad school forever – academics, that kind of thing. In New York, The Swarm was very collected in certain neighbourhoods, like Crown Heights, Central Brooklyn, Flatbush, but not so much in Harlem. Harlem, it’s more Buppies.”

It’s fascinating hearing Terence map his city in this way, describing in detail the way those communities rub up against each other while actively refuting the idea of blackness as a monolith. “I wrote a TV show about it and in the end, it was like The Swarm will die because we do not know how to integrate fluidly,” he says, deadpan. “Swarm ain’t havin’ no kids.”

A still from Random Acts of Flyness, courtesy of HBO.

Squeezed resources, rising rents, fracturing communities; these aren’t ideal conditions for making radical art. Yet Terence’s most recent project, the six-part HBO TV series Random Acts of Flyness, is just that – though Terence is reluctant to label his own work in this way. “I’ve never actually made anything radical,” he says. “To express something radical would mean taking away some of my ease in expressing it.” But that is not to say that the show could ever be considered ‘comfortable’.

Using sketch and satire to cover themes encompassing (among other things) police brutality and the capitalist peddling of white supremacy, Random Acts of Flyness is funny, jittery, sad and self-reflexive, cleverly interrupting itself in order to interrogate the effectiveness of its own politics. “I think at the end of the day you’re seeing us workshop a new methodology,” he explains. “The show is the process.”

A still from Random Acts of Flyness, courtesy of HBO.

As for the radical art that’s inspiring Terence at the moment? He finds himself looking backwards as much as forwards, but cites being moved and even startled by Milford Graves Full Mantis – a recent documentary about jazz percussionist, scientist and martial artist Milford Graves – as a perfect example.

“He’s kind of everything [at once],” says Terence. “It really affected me to see a black person – black power, of that generation – make it out intact. The sense in which he cultivated his spirit, or at the very least the way that it was captured in this movie… It gave me an example of the standard to which I should hold myself to.”

This article appears in Huck: The Flying Lotus Issue. Buy it in the Huck shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Follow @terenceetc on Instagram.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Capturing life in the shadows of Canada’s largest oil refinery

The Cloud Factory — Growing up on the fringes of Saint John, New Brunswick, the Irving Oil Refinery was ever present for photographer Chris Donovan. His new photobook explores its lingering impacts on the city’s landscape and people.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Susan Meiselas captured Nicaragua’s revolution in stark, powerful detail

Nicaragua: June 1978-1979 — With a new edition of her seminal photobook, the Magnum photographer reflects on her role in shaping the resistance’s visual language, and the state of US-Nicaraguan relations nearly five decades later.

Written by: Miss Rosen

A visual trip through 100 years of New York’s LGBTQ+ spaces

Queer Happened Here — A new book from historian and writer Marc Zinaman maps scores of Manhattan’s queer venues and informal meeting places, documenting the city’s long LGBTQ+ history in the process.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Nostalgic photos of everyday life in ’70s San Francisco

A Fearless Eye — Having moved to the Bay Area in 1969, Barbara Ramos spent days wandering its streets, photographing its landscape and characters. In the process she captured a city in flux, as its burgeoning countercultural youth movement crossed with longtime residents.

Written by: Miss Rosen

In photos: 14 years of artist Love Bailey’s life and transition

Dancing on the Fault Line — Photographer Nick Haymes’s new book explores a decade-plus friendship with the Californian artist and activist, drawing intimate scenes from thousands of pictures.

Written by: Miss Rosen

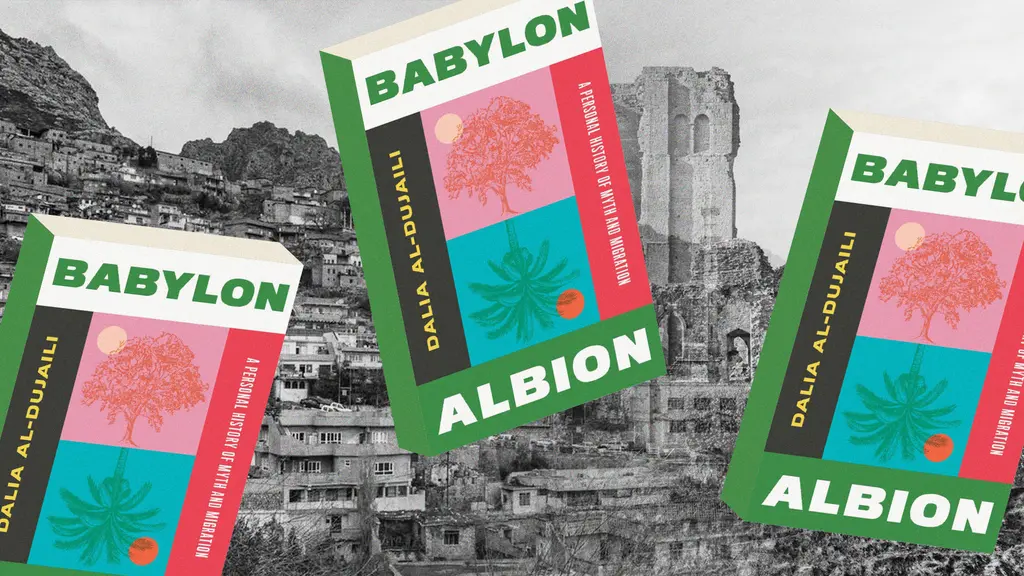

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori