How coder Zach Sims realised his dream of never working for anyone

- Text by Rob Boffard

- Photography by Bryan Derballa

For as long as he can remember, Zach Sims always knew he wanted to work for himself.

He’d spent plenty of time working for others, interning each summer at tech companies while studying political science at Columbia University. It was good experience, but never enough. Along with his friend Ryan Bubinski, Zach was itching to get going − but unsure where to start. “Ryan and I realised that there was a huge gap between the skills people needed to find jobs and skills they were being taught in modern educational institutions,” says Zach. “We saw this problem first-hand, and decided to solve it.”

They weren’t going to solve it at Columbia. In 2011, Zach and Ryan upped sticks for California’s vibrant start-up culture. Brimming with ideas, they joined the prestigious Y-Combinator group, an accelerator for tech companies. But there was one big problem: Zach Sims couldn’t code.

It’s not like he didn’t try – every night, every weekend, using all the material he could find, running through Javascript and JQuery until all he could see were code strings. “I was exhausted and stressed,” he says. “I was watching a bunch of videos, reading textbooks, and getting really frustrated by the difficulty. I wanted to learn to code so that I could contribute to the project that we were building.”

Zach came to a realisation. The ideas they were developing through Y-Combinator weren’t working. “They were all focused on solving the same problem but taking different approaches,” he says. “It was months of trial and error. We knew at the beginning the problem we wanted to solve, which was to teach people the skills they needed to find jobs. But the approach we were taking to do that was less clear.”

And yet here he was, busting his gut every night, a victim of the very same problem that brought them to Cali in the first place. Then Zach had an epiphany: What if there was an easy way to learn to code? Something anyone could use with zero experience?

Y-Combinator is a high-pressure, demanding environment, but it fosters good ideas. This was clearly one of them. “We focused on building the first version of the product that we wanted,” Zach explains. “It took a couple of different iterations in order to end up with Codecademy.”

Zach and Ryan built, tested, and rebuilt their online platform. In August 2011, they were ready to launch. Nobody could have predicted exactly what would happen next.

The uptake was staggering. By the end of launch weekend, 200,000 people had taken advantage of the Codecademy website’s simple lessons. It was never, Zach says, a sure thing. “We were absolutely worried [about failing],” he admits. “We thought we were building something that would be reasonably popular, but we had no idea that it would end up growing into what it has grown into. It was a surprise.”

Four months later, Zach and Ryan took Codecademy to New York. At the time of writing, over 25 million people, including former New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg and President Obama, have taken its free lessons.

Zach not only ended up working for himself, he found a way to help millions of people follow that same path.

Asked what advice he’d give to his younger self – someone itching to get out there and make it on their own – he’s characteristically direct. “I’d tell myself to continue to learn as fast as possible, and really think about developing frameworks for ideas instead of relying on experience, and gathering lots of data before making a decision. The eighteen-year-old version of me wanted to be where I am now, so I think he would have listened.”

This article originally appeared in How To Make It On Your Own, a handbook for inspired doers from Huck’s 50th Issue Special.

Subscribe today to make sure you don’t miss another issue.

You might like

Capturing life in the shadows of Canada’s largest oil refinery

The Cloud Factory — Growing up on the fringes of Saint John, New Brunswick, the Irving Oil Refinery was ever present for photographer Chris Donovan. His new photobook explores its lingering impacts on the city’s landscape and people.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Susan Meiselas captured Nicaragua’s revolution in stark, powerful detail

Nicaragua: June 1978-1979 — With a new edition of her seminal photobook, the Magnum photographer reflects on her role in shaping the resistance’s visual language, and the state of US-Nicaraguan relations nearly five decades later.

Written by: Miss Rosen

A visual trip through 100 years of New York’s LGBTQ+ spaces

Queer Happened Here — A new book from historian and writer Marc Zinaman maps scores of Manhattan’s queer venues and informal meeting places, documenting the city’s long LGBTQ+ history in the process.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Nostalgic photos of everyday life in ’70s San Francisco

A Fearless Eye — Having moved to the Bay Area in 1969, Barbara Ramos spent days wandering its streets, photographing its landscape and characters. In the process she captured a city in flux, as its burgeoning countercultural youth movement crossed with longtime residents.

Written by: Miss Rosen

In photos: 14 years of artist Love Bailey’s life and transition

Dancing on the Fault Line — Photographer Nick Haymes’s new book explores a decade-plus friendship with the Californian artist and activist, drawing intimate scenes from thousands of pictures.

Written by: Miss Rosen

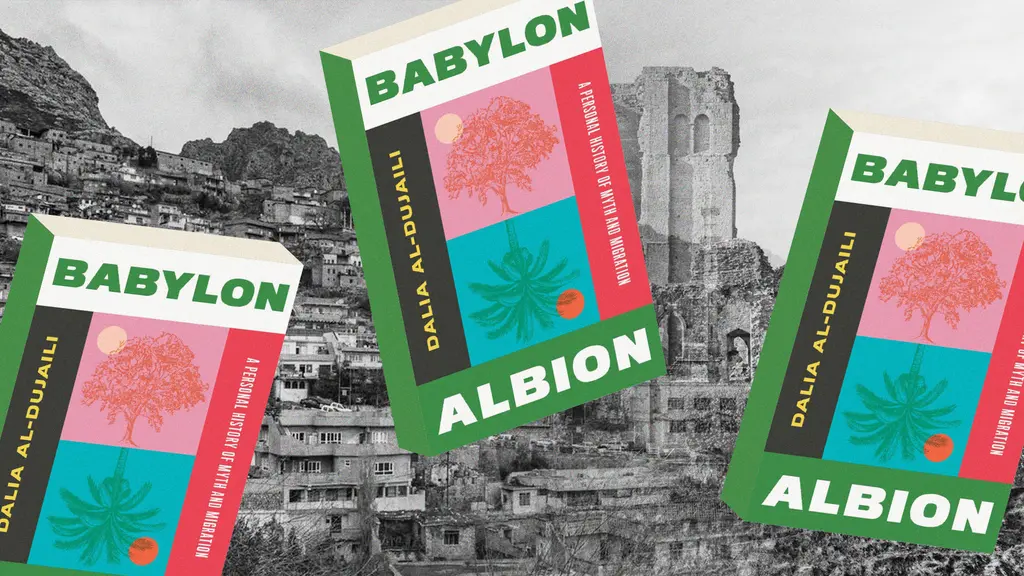

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori