Transformative Books

- Text by HUCK HQ

Books change lives. Period. Maybe it was that book you read as a teenager that made you feel like somebody really understood what you were feeling for the first time in your life. Perhaps it was the one you read working some shitty job that finally made you say: “Fuck it, I quit! I’m heading out on the open road to live my dreams!” Or maybe it was the novel that made you look at your life differently, seeing the world and the people around you in a completely new light. For all of us, there are those special pieces of literature that have the power to radically alter the course of our existence. To celebrate World Book Day, Huck shares some of the books that never left us. Read them, and maybe they’ll never leave you.

The Dharma Bums by Jack Kerouac

Contributor: Michael Fordham

Hometown: London

I picked up a dog-eared yellow-papered copy of Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums on the book swap shelf of a shitty old-man hotel in Denver, Colorado. I was eighteen and it was 1986 and at the time I’d never heard of the Beats or Kerouac, but I was unwittingly going through my own Beat period – hitching and hopping buses with pack on my back not really caring where I was ending up. The soaring simplicity of the storytelling looks naive and pie-eyed through the gauze of the years – but at the time and in that place the book spoke directly to my heart. The Dharma Bums lived for the now and were mad to delve into the raw planet’s pleasures – engaging their body as well as their minds in a joyful expectation of the possible. I’ve strived to live with that open-hearted way of apprehending the world ever since.

“I felt like lying down by the side of the trail and remembering it all. The woods do that to you, they always look familiar, long lost, like the face of a long-dead relative, like an old dream, like a piece of forgotten song drifting across the water, most of all like golden eternities of past childhood or past manhood and all the living and the dying and the heartbreak that went on a million years ago and the clouds as they pass overhead seem to testify (by their own lonesome familiarity) to this feeling.”

Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon

Contributor: Tetsuhiko Endo

Hometown: London, by way of Ohio

I was in Uruguay working with street children and feeling deliciously jaded about the evils of the world when my brother mailed me a copy of Gravity’s Rainbow. It taught me that whatever evil you think you’ve seen, you ain’t seen shit: the world works in far, far nastier ways than you can ever imagine. There is a strange sort of power that comes with accepting that: a lot of possibilities open up to you creatively, professionally, personally. As Pynchon says, “You may never get to touch the Master, but you can tickle his creatures.”

The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy

Contributor: Monisha Rajesh

Hometown: London

I first read The God of Small Things fifteen years ago, just before it won the Booker. It felt like the moment when Lucy pushes through the fur coats in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and finds an unknown world beyond.

Roy showed me how words could move and dance and sing and stand together in ways that I had never known. And she made me see that there were no rules or restrictions on how language could be bent, shaped and stretched. She made me want to write.

An extract from a scene where the tiny Rahel observes her great aunt having a wee: “Rahel held her handbag. Baby Kochamma lifted her rumpled sari… Baby Kochamma balanced like a big bird over a public pot. Blue veins like lumpy knitting running up her translucent shins. Fat knees dimpled. Hair on them. Poor little tiny feet to carry such a load! Baby Kochamma waited for half of half a moment. Head thrust forward. Silly smile. Bosom swinging low. Melons in a blouse. Bottom up and out. When the gurgling, bubbling sound came, she listened with her eyes. A yellow brook bubbling through a mountain pass. Rahel liked all this. Holding the handbag. Everyone pissing in front of everyone. Like friends. She knew nothing then of how precious a feeling this was. Like friends. They would never be together like this again.”

Light Years by James Salter

Contributor: Joe Donnelly

Hometown: Los Angeles

A friend gave me this book, coincidentally, when the structures of the life I’d been leading for nearly a decade came tumbling down. He didn’t know that was what was going on in my life, but it happens the novel deals with the unravelling of an idyllic marriage and life. I read about this house coming apart while mine was being packed up in boxes. Testament to Salter that I couldn’t stop reading despite all that. Looking back, it’s kind of hilarious.

“There are really two kinds of life. There is, as Viri says, the one people believe you are living, and there is the other. It is this other which causes the trouble, this other we long to see.”

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

Contributor: Adam Woodward

Hometown: London

I’ve been fascinated with American history, particularly from the first half of the twentieth century, from a young age. As a teenager John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath opened up that world to me in a more profound way than any schoolbook I could lay my hands on. It was the first time I remember thinking that fiction could be immersive, evocative and educational all at the same time.

“How can you frighten a man whose hunger is not only in his own cramped stomach but in the wretched bellies of his children? You can’t scare him – he has known a fear beyond every other.”

The Plague by Albert Camus

Contributor: Andrew Binion

Hometown: Brooklyn, NYC

At twenty-five I read The Plague by Albert Camus. It is a great book, but a single line stuck. I was sitting in an airport in New York City, no fixed address, no money, no sleep, sprained ankle, I hadn’t eaten for a day and wouldn’t until I arrived back in Seattle. I had thrown away my life, yet again, crossed the continent to the big city to find my fortune and lasted two weeks. Now I was retreating on a ticket bought with borrowed money. I came across this line: “Love asks something of the future.” I underlined it, copied it into my journal, kept it in my head. Back in Seattle, I fell for a girl, enrolled in university, visited my parents, and for the most part kept my distance from freight trains.

Animal Liberation by Peter Singer

Contributor: Jon Coen

Hometown: Long Beach Island, NJ

When we were young, two friends and I drove down to Central America and spent the winter living in a van. Right before we left the US, I bought Animal Liberation by Peter Singer from a used bookstore in Arizona, written the year I was born. We had a very visceral lifestyle, closer to our food sources than usual. I was already a pescatarian and most of the information I had was from the hardcore scene, but Singer really opened my eyes to the health, enviro and ethical issues of agribusiness. I wound up eating a lot of rice and beans, but at least I didn’t get duped into goat quesadillas and I still have that copy of the book.

“Forests and meat animals compete for the same land. The prodigious appetite of the affluent nations for meat means that agribusiness can pay more than those who want to preserve or restore the forest. We are, quite literally, gambling with the future of our planet – for the sake of hamburgers.”

Plexus by Henry Miller

Contributor: Jamie Brisick

Hometown: New York City

Plexus by Henry Miller helped me to discover who I was and what I wanted in my life. I read it in my mid-twenties when I was a Yank living in Sydney. My pro-surfing career had recently declared bankruptcy and my first love had recently collapsed. I was lost, stoned, wounded. It was this kind of stuff that leapt off the page at me:

“Suffering is unnecessary. But, one has to suffer before he is able to realise that this is so. It is only then, moreover, that the true significance of human suffering becomes clear. At the last desperate moment – when one can suffer no more! – something happens which is the nature of a miracle. The great wound which was draining the blood of life closes up, the organism blossoms like a rose. One is free at last, and not ‘with a yearning for Russia,’ but with a yearning for ever more freedom, ever more bliss. The tree of life is kept alive not by tears but the knowledge that freedom is real and everlasting.”

Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke

Contributor: Noah Hussin

Hometown: Asheville, NC

Resting in Mississippi during our bicycle trip, we encountered an enthusiastic young man with endless questions and unflinching eye contact. Insisting he had something I needed, he demanded I close my eyes. A slim book fell softly into my hands. Absorbing its intimidating eloquence under the stars, I realised how eager I had become to define our story and impose order over its chaos. Rilke’s tempered wisdom reminded me once again that destination is a mere byproduct of journey, and utterly meaningless without it.

“I beg you to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don’t search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them – and the point is to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.”

Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller

Contributor: Shane Herrick

Hometown: London, by way of NYC

I first read Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer when I was around seventeen. I was nearing the end of high school in New York with a head full of Bad Brains. America was at war again – still is – and I was debating university in the face of an increasingly doomed economy and uncertain future. In these lines, I found a familiar approach to uncertainty under the ever-present spectre of modern disaster. I found unique, eternal optimism despite it all, comfort in conviction and found wealth of the kind that can’t be bought. Miller exposed a new way to write, a new way to read, a new way to live.

“I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive. […] This is not a book. This is libel, slander, defamation of character. This is not a book, in the ordinary sense of the word. No, this is a prolonged insult, a gob of spit in the face of Art, a kick in the pants to God, Man, Destiny, Time, Love, Beauty… what you will. I am going to sing for you, a little off-key perhaps, but I will sing. I will sing while you croak, I will dance over your dirty corpse. […] It is not necessary to have an accordion, or a guitar. The essential thing is to want to sing. This then is a song. I am singing.”

The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by Tom Wolfe

Contributor: Cyrus Shahrad

Hometown: London

I came across Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test as an Englishman in New York, where I’d retreated for three months in 1998, aged nineteen, after an ill-advised summer job in Nashville fell through. My psychedelic sense was already tingling, but it took Wolfe’s crazed descriptions of Kesey’s acid odyssey to convince me that the hallucinogenic experience deserved my undivided attention.

“And Sandy takes LSD and the lime :::::: light :::::: and the magical bower turns into… neon dust… pointless particles, brilliant forest-green particles, each one picking up the light, and all shimmering and flowing like an electronic mosaic, pure California neon dust. There is no way to describe how beautiful this discovery is, to actually see the atmosphere you have lived in for years for the first time and to feel that it is inside of you too… he and George Walker are in the big tree in front of the house, straddling a limb, and he experiences… intersubjectivity – he knows precisely what Walker is thinking. It isn’t necessary to say what the design is, just the part each will do. ‘You paint the cobwebs,’ Sandy says, ‘and I’ll paint the leaves behind them.’”

Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Contributor: Bill Cotter

Hometown: Austin, Texas

Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment was the only book in the smoking room of a psychiatric hospital in which I spent a fairly unpleasant two and a half years or so back in the mid-1980s. And even though the boredom in that place hourly tested one’s mortality, the image on the cover of that book – an impressionistic portrait in raw umber of a slumped depressive with an oily beard – and the book itself – stained, torn, creased, a fluorescing orange price sticker at hideous odds with the otherwise shadowy palette – was so repulsive that I always turned instead to its only reading alternative: stacks of ancient housekeeping magazines. But one day the magazines were not there. I was out of cigarettes. I opened Crime and Punishment. Soon I was not where I was, but rather in mid-Nineteenth Century St. Petersburg, its icy garrets, inebriation, street odours, dram-shops and taverns, in all their sublime dreariness, far more inhabitable than anywhere I’d ever been. I stole that copy from the smoking room and ran away, imagining that I might someday be able to write escapes for others.

“Don’t be overwise; fling yourself straight into life, without deliberation; don’t be afraid – the flood will bear you to the bank and set you safe on your feet again.”

Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees by Lawrence Weschler

Contributor: Andrew Kenney

Hometown: Brooklyn, NYC

Since I was young I always loved reading biographies and seeing how and why other people’s lives developed. My favourite biography of an artist is about Robert Irwin, Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees by Lawrence Weschler. There’s a particular moment where Robert goes into isolation for eight months and I can relate to it in many different ways.

“It was a tremendously painful thing to do, especially in the beginning. It’s like in the everyday world you’re just plugged into all the possibilities. Every time you get bored, you plug yourself in somewhere: you call somebody up, you pick up a magazine, a book, you go to a movie, anything. And all of that becomes your identity, the way in which you’re alive. You identify yourself in terms of all of that. Well, what was happening to me as I was on my way to Ibiza was that I was pulling all those plugs out, one at a time: books, language, social contacts. And what happens at a certain point as you get down to the last plugs, it’s like the Zen of having no ego: it becomes scary, it’s like maybe you’re going to lose yourself. And boredom then becomes extremely painful. You really are bored and alone and vulnerable in the sense of having no outside supports in terms of your own being. But when you get them all pulled out, a little period goes by and then it’s absolutely serene, terrific. It just becomes really pleasant, because you’re out, you’re all the way out.”

This feature first appeared in Huck 35 – The On The Road Issue. To read the full article and discover more life-changing works of literature, grab a copy here.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Capturing life in the shadows of Canada’s largest oil refinery

The Cloud Factory — Growing up on the fringes of Saint John, New Brunswick, the Irving Oil Refinery was ever present for photographer Chris Donovan. His new photobook explores its lingering impacts on the city’s landscape and people.

Written by: Miss Rosen

Susan Meiselas captured Nicaragua’s revolution in stark, powerful detail

Nicaragua: June 1978-1979 — With a new edition of her seminal photobook, the Magnum photographer reflects on her role in shaping the resistance’s visual language, and the state of US-Nicaraguan relations nearly five decades later.

Written by: Miss Rosen

A visual trip through 100 years of New York’s LGBTQ+ spaces

Queer Happened Here — A new book from historian and writer Marc Zinaman maps scores of Manhattan’s queer venues and informal meeting places, documenting the city’s long LGBTQ+ history in the process.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Nostalgic photos of everyday life in ’70s San Francisco

A Fearless Eye — Having moved to the Bay Area in 1969, Barbara Ramos spent days wandering its streets, photographing its landscape and characters. In the process she captured a city in flux, as its burgeoning countercultural youth movement crossed with longtime residents.

Written by: Miss Rosen

In photos: 14 years of artist Love Bailey’s life and transition

Dancing on the Fault Line — Photographer Nick Haymes’s new book explores a decade-plus friendship with the Californian artist and activist, drawing intimate scenes from thousands of pictures.

Written by: Miss Rosen

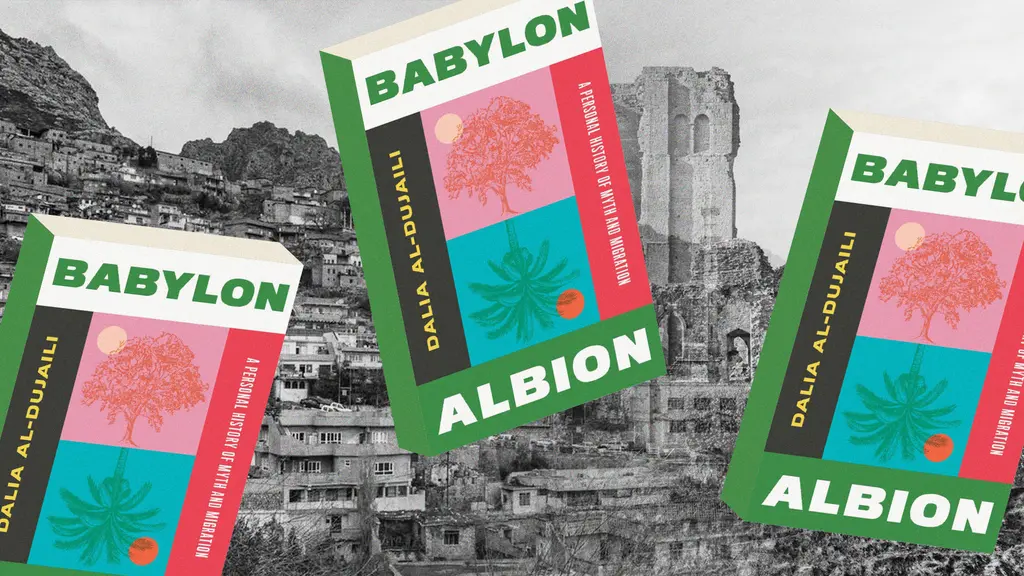

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori