Why we must reclaim our right to roam the land

- Text by Nick Hayes

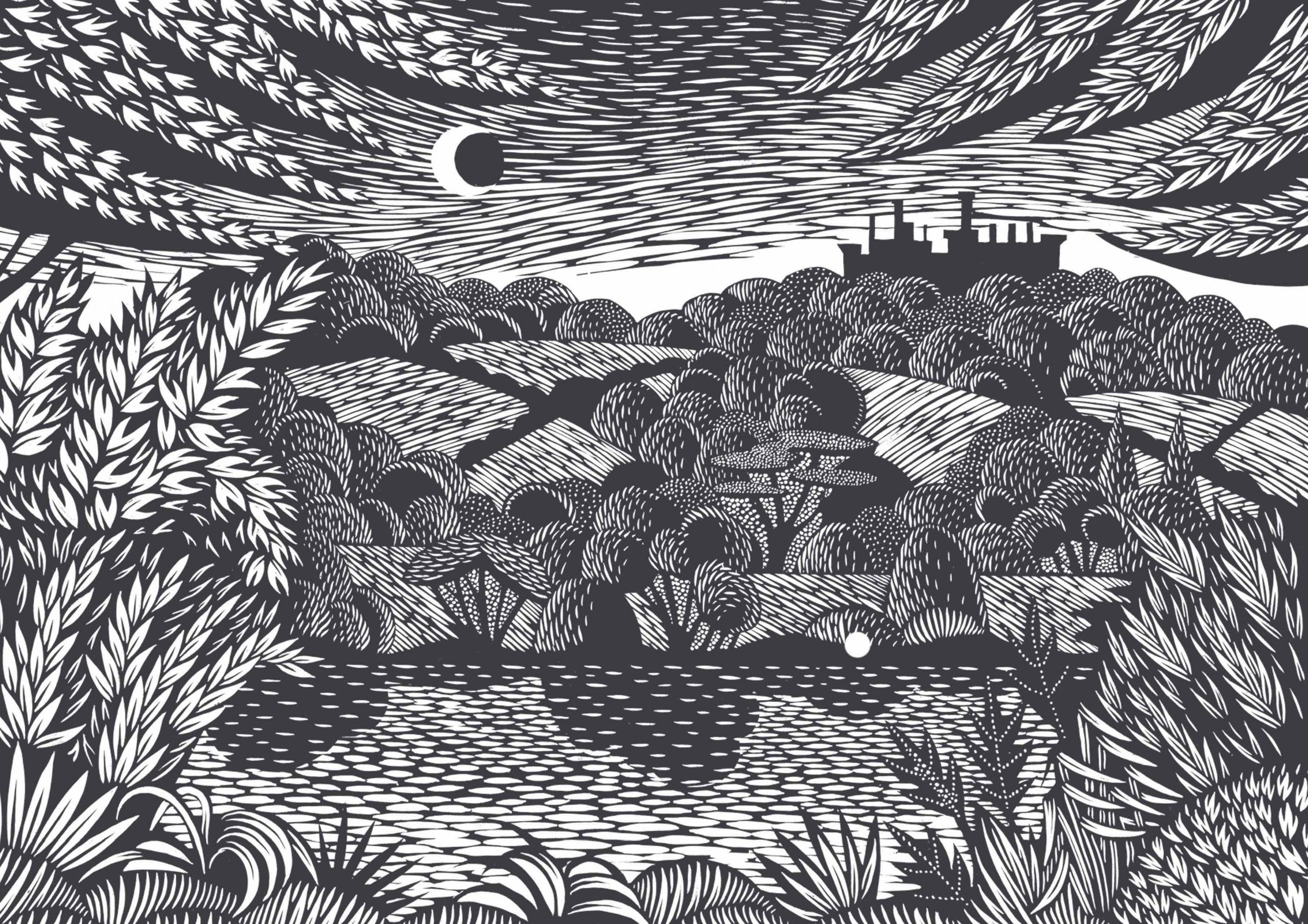

- Illustrations by Nick Hayes

The countryside is a grid of power and authority. Just as the land is controlled by an elite few, so is the society which has nowhere else to be but the land. It is corralled and commanded by a system that gives rights to those that own land, and takes them from those that don’t.

Unlike the power lines that run above our heads, which distribute electrical power to all of England, these barbed wire lines channel societal power, wealth and health, from the people who live around them, into the hand of the oldest elite in history – the lords of the land, the landlords.

The way we define property in England allows exclusive dominion over the land. If you own a portion of England, you are allowed to exclude all others from it, farm it, mine it and even destroy it, regardless of the ecological impact of your work, or the wider, societal impact of a public partitioned from nature.

Property law is stuck together with a sticky tape known as ‘legal fiction’, in other words, “an assertion that is accepted as true for legal purposes, even though it may be untrue or unproven”. Property pretends that walking through an estate of 20,000 acres, say a grouse moor in the Pennines, is the same as leaping over a fence into someone’s suburban back garden.

In law they are the same thing, in reality, they are palpably different. But because property law also pretends that a person’s property is an extension of their self, every incursion onto land you don’t own is classed as a tort – that is, a direct harm to the owner. Whether you cause damage or not, the law treats trespass not as an act of digression, but of aggression. If there is harm in trespass, however, it is not to the owner, but to the society that are excluded from the physical and mental health benefits of nature. But for some reason, we just let it be.

The walls that divide us from nature are manifestations of a status quo: that an elite few deserve a bigger and better portion of the world than the majority. The laws that legitimise them are outmoded archaic laws, palimpsests of self-interested legislation forged by French invading barons, Tudor lawyers and the cabal of Georgian landowners otherwise known as the unreformed parliament.

The walls that divide us from nature are manifestations of a status quo: that an elite few deserve a bigger and better portion of the world than the majority. The laws that legitimise them are outmoded archaic laws, palimpsests of self-interested legislation forged by French invading barons, Tudor lawyers and the cabal of Georgian landowners otherwise known as the unreformed parliament.

They were built out of self-interest, a desire to privatise the commonwealth to line private pockets, a process described by David Harvey as “accumulation by dispossession”. To put a wall up around what was previously common ground is to take the wealth of the land, shared by its commoners, and siphon it into your own pockets.

But historically, these walls did a lot more than that: they not only divorced the English working class from their means of subsistence (hunting became poaching, collecting firewood become trespass and theft), in many cases it also left them homeless – squatting on the sides of fields or wandering the roads to be rounded up by any number of vagrancy acts first established in 1349, and dumped in the workhouse. They also severed communities ties with nature, and with each other.

Yet today these walls stand with an authority that is rarely questioned, almost never contravened, the history of their imposition masked by something that sociologists call ‘conceptual conservatism’ (the ability to maintain an acceptance of ideology even in the face of evidence that unquestionably undermines it).

But what if you climb those walls? What if you climb over their stony-faced authoritarian glare, and look behind them to the dark source of their power?

But what if you climb those walls? What if you climb over their stony-faced authoritarian glare, and look behind them to the dark source of their power?

For two years, researching The Book of Trespass, this is exactly what I did: hopping the walls of the lords, politicians, media magnates and private corporations that own England, walking in the woods, swimming in the rivers and lakes, camping in the meadows that are banned from public access. The book is ostensibly an argument for how we, the public, should have a greater right of access to nature, how (like our neighbours in Scotland, Norway or Sweden) the right of ownership should be superseded by the right of public access.

So for two years, I pretended that England also had a right to roam, and I followed the responsibilities laid out by the Scottish version – never went near a private garden, never left a single trace of my visit. In Scotland, every trip I made would have been perfectly legal, yet in England, this free connection with nature is criminalised.

Trespass is an act that breaches a societal norm rooted deep in English culture, that the value of the land should belong exclusively to those who own it, and not to the communities that so badly need it. But to climb the walls that were built around our common land is to challenge an even deeper consensus: it questions the legitimacy of the castle that built these barriers in the first place, the laws that were constructed to defend them and the entire dynamic of elite power that defines and confines the freedoms of the wider community.

Trespass shines a light on the unequal share of wealth and power in England, it threatens to unlock a new mindset of our community’s rights to the land, and, most radical of all, it jinxes the spell of an old, paternalistic order that tell us everything is just as it should be.

The Book of Trespass is out now on Bloomsbury.

The Book of Trespass is out now on Bloomsbury.

Follow Nick Hayes on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Inside the obscured, closeted habitats of Britain’s exotic pets

“I have a few animals...” — For his new series, photographer Jonty Clark went behind closed doors to meet rare animal owners, finding ethical grey areas and close bonds.

Written by: Hannah Bentley

The rebellious roots of Cornwall’s surfing scene

100 years of waveriding — Despite past attempts to ban the sport from beaches, surfers have remained as integral, conservationist presences in England’s southwestern tip. A new exhibition in Falmouth traces its long history in the area.

Written by: Ella Glossop

The British intimacy of ‘the afters’

Not Going Home — In 1998, photographer Mischa Haller travelled to nightclubs just as their doors were shutting and dancers streamed out onto the streets, capturing the country’s partying youth in the early morning haze.

Written by: Ella Glossop

The Chinese youth movement ditching big cities for the coast

In ’Fissure of a Sweetdream’ photographer Jialin Yan documents the growing number of Chinese young people turning their backs on careerist grind in favour of a slower pace of life on Hainan Island.

Written by: Isaac Muk

We Run Mountains: Black Trail Runners tackle Infinite Trails

Soaking up the altitude and adrenaline at Europe’s flagship trail running event, high in the Austrian Alps, with three rising British runners of colour.

Written by: Phil Young