The street studio where anybody can sit for a portrait

- Text by Alexia Webster

- Photography by Alexia Webster

This story appears in The Documentary Photography Special VII. Get your copy now, or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

In my childhood home, there was an old black-and-white photograph that used to hang in the hallway. It was a family portrait – of my grandparents, my great uncles and my mother as a three-year-old, all posing in a photographer’s studio.

At the time, they were going through a lot of upheaval – they were recent economic migrants who’d moved from a small island in Greece to South Africa – but all you could see was their pride; their elegance. It’s an amazing, dignified image. Of all the photographs I have, it’s the one I treasure most.

When I was a teenager, South Africa was going into democracy – the world was being explained to me in this incredible way through photography. I decided that was the kind of thing I wanted to do. Eventually, I started working as a photojournalist and was doing a lot of work in refugee camps. In 2011, I arrived in this camp in Kenya called Kakuma to document work being done by an NGO.

One day when I was shooting, an Ethiopian man came up to me and said, ‘So, when are we going to see these photographs?’ I replied, ‘Well, to be honest, I don’t think you are going to get to see them.’ Understandably, he was super annoyed. There had been a lot of photojournalists coming in and out of the camp, taking photographs that none of the subjects ever got to see. This man – himself a refugee – told me that he didn’t have pictures of his own family. Meanwhile, he was on parade for photos that he would never see.

This really resonated with me – given how much I value my own family photos. I realised then that a lot of the images I took may be looked at briefly by audiences around the world and then quickly discarded, but to the people in them, they were valuable and important. In the context of that refugee camp, where many people have lost their sense of home, a family photo takes on a whole new meaning.

Neema Bonke, 35, pregnant with her third child, poses for a photo in Bulengo IDP Camp in Goma, DR Congo. March 2014.

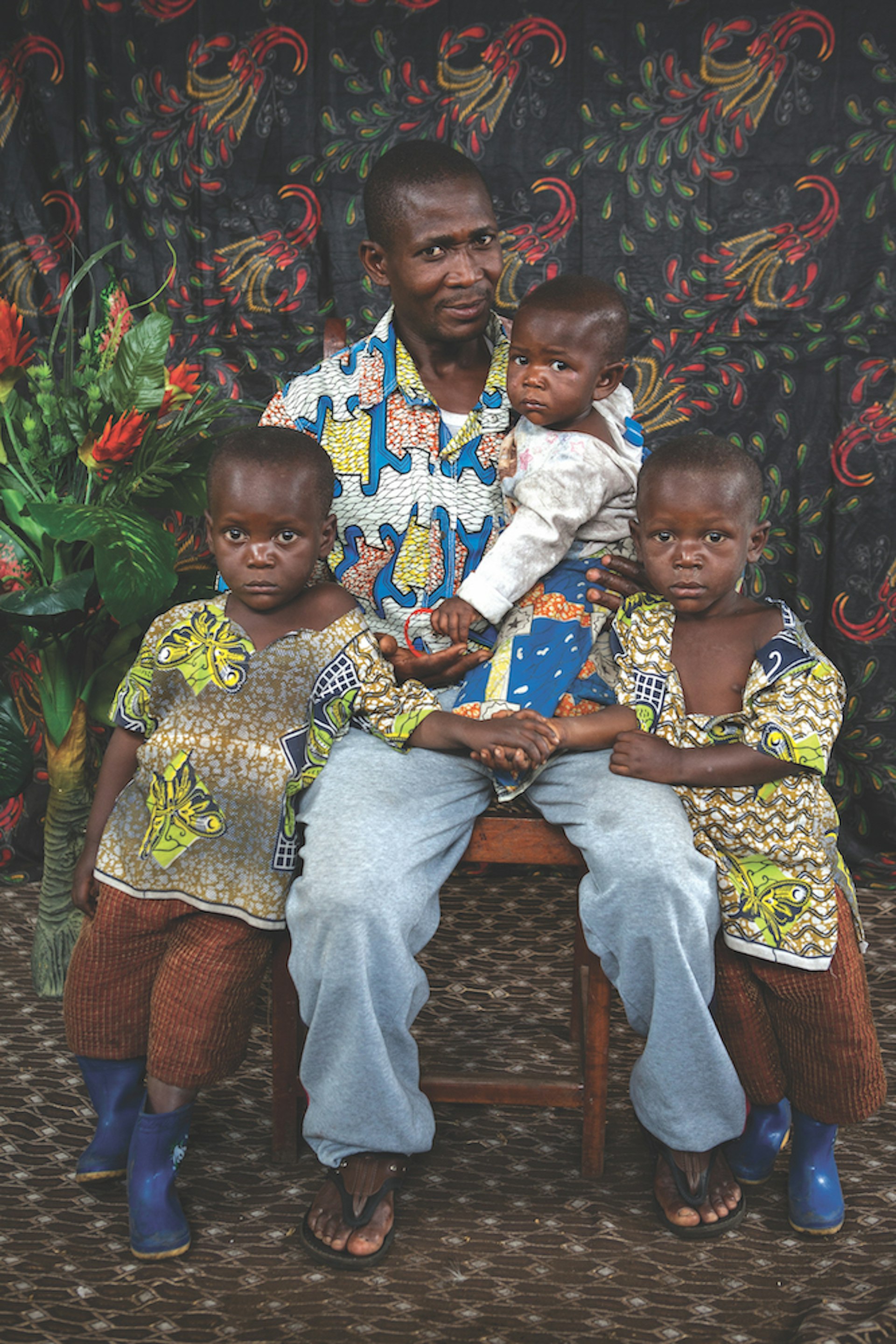

A father and his three children pose for a portrait at the Bulengo IDP Camp in Goma, DR Congo. March 2014.

Back at home in Cape Town, there are guys who walk around on a Saturday night taking photos of people out on the town and carrying portable printers. When I saw this, I remembered that man in the camp and the idea of Street Studios was born. The first one I did was in Cape Town in 2011. Together with my friend and very talented artist Michael Saal we set it up in a neighbourhood near my studio and had a line of people queuing for about two days. People brought their families and waited for ages to have their picture taken. For me, the experience was very moving.

Since then, if I’m ever working in a place where I feel like it could be valuable, I try and spend an extra day there and set up a studio. I’ve done it in Mexico, India, Madagascar, South Africa, the USA and South Sudan as well as in refugee camps in the DRC. I’ve taken thousands of photographs around the world.

Most of my subjects pose as a family. But even when people pose alone, it’s about a sense of belonging: ‘I am here, I mean something, I belong to this human race. My life is of value.’ That’s why the family photograph in my home resonated so much – these were my ancestors, I was part of this story.

A young woman poses at a studio in the neighbourhood of Camino Verde, Tijuana, Mexico. July 2017.

There are mixed reactions when people see a photo of themselves. Mostly it’s really beautiful. But perhaps the most interesting response I had was in a refugee camp in Congo. A woman sat for a portrait and she had a huge scar over her face; I later learned that her husband had been murdered and she had been attacked when her village was forced to flee a militia attack. She posed, I took the photo, then she left.

I carried on photographing and then took a break. I went outside and there was a gathering of people. The woman was in the middle and she was very upset: it transpired that she hated the way she looked in the photograph. I said, ‘It’s fine, we can retake it!’ But the group of women who had gathered around her explained that it wasn’t the photo that was the problem. She had simply never seen herself since the attack and the photo had forced her to confront what had happened. The women reassured me, ‘It’s fine, continue photographing, we’ve got this,’ as they offered her support – talking through what she was feeling as a collective, and processing the trauma. It became a powerful experience.

For me, it all comes back to this idea of belonging. People will borrow clothes from one another so they can look smart for their portrait. They hang around the studio, interacting as they wait to get their picture taken. It becomes this public performance of love and identity. I think that’s what gives it the magic I feel in it.

Two friends pose at the first Street Studio in Woodstock. Cape Town, South Africa. March 2011.

Bariki Bahati, 19, poses for a portrait in Bulengo IDP Camp, Goma, DR Congo. March 2014.

Akili, 3 months old, is the daughter of Mapenzi Mwamini, 18. The family were farmers in Masisi before coming to Bulengo IDP Camp, Goma, DR Congo. March 2014.

Nircina Rasoarinalala, 12, and her brother Njara, 1, the children of workers at the Ambohitrombihavana granite rock quarry, Madagascar, as their parents break rocks. October 2014.

This story appears in The Documentary Photography Special VII. Get your copy now, or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

See more of Alexia Webster’s work on her official website.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.