How to escape the tyranny of work under capitalism

- Text by Daisy Schofield

- Illustrations by Pluto Press

Let’s face it: work isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. For a generation faced with less opportunities, less security and less pay, the many lies sold to us about work have been shattered. And yet, with so much of our identities bound up with our jobs – we do, after all, spend a third of our lives at work – it can be hard to envisage an alternative.

Writer and researcher Amelia Horgan’s new book, Lost in Work: Escaping Capitalism (Pluto Press), sets out to debunk work’s fantasy, and to offer a radical new vision of what society could look like. In the context of Covid-19 – which has led to staggering levels of unemployment and seen workers exposed to vastly different levels of risk – its release could not feel more timely.

Huck spoke to Amelia about coming to the realisation that work does, in fact, suck, rethinking unemployment, and why unions must be at the heart of every organisation.

You started writing Lost in Work before Covid-19. Did the pandemic shape the outcome of this book?

I think the conclusions of the book would have been the same before Covid. But one thing that the pandemic threw into sharp relief is the relationships of power at work. And I think that, in some ways, it made the book an easier case to make, because the mythology of work was kind of punctured. This ‘we are a family’ stuff doesn’t really hold when people are being made to go into really dangerous working environments.

In terms of my own kind of experience with the book, people often expect a confession of being an overproductive person or someone who is too into hustle culture. Even though that’s a very common kind of pathology, I am completely the opposite. I’m a fundamentally lazy person, so it didn’t really cause me to reassess my relationship to work. [Laughs]

When did you start to realise that work, as we currently know it, sucks?

For me, it was in those first jobs as a teenager. I was working for a catering agency and you’d have to arrive at some horrible o’clock. Once, we had to go to this person’s house dressed up in morph suits. [We felt like] there has to be a better way of organising human life than this!

Whereas in the office jobs I’ve had, I’ve been quite lucky, in that I’ve had the kinds of jobs that are meaningful – so charity or third sector kind of stuff. But I think there’s still a fantasy of working life where you go in and you’re wearing the perfect office wear, and it’s all sleek and stylish, and you do a really good elevator pitch, or a really good report… I remember finding that my experience of the office was very different to that.

But it was more those early experiences with service work, where the naked power relations are often pretty visible [that made me realise work sucks]. Especially where there’s gender dynamics at play, because of just how routine sexual harassment is.

So many jobs, such as hospitality, have become so much harder during the pandemic, with staff becoming rule-enforcers, essentially.

It’s really awful, and something I’ve been thinking about in terms of returning to face-to-face teaching at university, and how much the expectation would be that academics have to police students. And, how awful that is for social relations if you’re bar staff or an Uber driver.

Having to police people, especially if you don’t have very much power, and especially in that really precarious gig work, where your future ability to get work depends on your online rating… you just are not necessarily going to be in a position to say ‘no’. That’s the kind of the tyranny of the customer ‘always being right’, which is made so much more powerful by this platform gig work.

You include quite a surprising stat at the beginning of the book about a 2017 poll which found that two thirds of people in the UK claim to like or love their job. Why was that stat important to include?

I include that stat because I think it’s really important for people who are critics of work and of capitalism to reckon with. People do report enjoying their work. So what does that mean? There are a few ways you could approach it.

One, is that people find things enjoyable in their work that aren’t necessarily really to do with their work: it might be that they get on with their colleagues, they go to the pub after work, or it might be that there are elements of a job which they find rewarding.

The other point is that we don’t have many other opportunities for self-fulfillment, and for developing ourselves, other than work. So much of our lives is at work: especially now, where people often work across multiple jobs, or in precarious work, where people are worried about what job is coming next. So, work time is not just literally the time you spend at work.

So there’s a question around that: What would people do instead [of work]? I think it’s important for critics of work under capitalism not to be prescriptive or moralistic about what people can be doing. But I think there are all kinds of other ways of being together, other ways of creating and living together. This kind of stuff is suppressed, or the possibilities for them are reduced, in contemporary capitalism.

That’s an important element of why it is that people find enjoyment in work as well, because there’s not necessarily much else to find enjoyment in.

How has this sense that you should love your job only made things worse for workers?

That element is really important. This idea that we find freedom through the market and we realise ourselves through the jobs available to us is common, but it takes on perhaps a particularly pernicious form when it comes with these jobs that we’re supposed to love.

You can see that this kind of stuff is thrown back in the face of workers when they’re trying to organise. [It’s the idea that] ‘If you really cared about this organisation, or this cause you’re working for, you wouldn’t go on strike’, ‘Do you not care about this?’… Or, if you love your job, you would stay longer, you would work for free.

It stops you seeing yourself as a worker, and this is something I see in academia a lot. It’s not limited to that, of course, but it’s very common.

The conversation around a four-day week is often accompanied by an argument that it will make workers more productive on the days they do work. In this sense, do such solutions sometimes miss the point?

I think one thing that’s important with demanding less working time is that it has to come without a reduction in wages. It has to be the same conditions, but less time. A good thing about a four-day week is that that extra time could also be put to other political use. One of the things that genuinely really hinders social movements, or the organised left, is that people have to work so much and don’t always know when they won’t be working – the stats on the number of people who don’t know when their next shift will be is really huge.

We can put that time to good use; it’s not about demanding it so we can all go to meetings on our extra day off. And a lot of the attacks on our time are attacks on our freedom to organise as well as our ability to have leisure. I think framing a four-day week in those terms can be really helpful, too. Because people have had a four-day week, with bank holidays, it’s one of those demands that has a concreteness and tangibility to it.

There is never going to be one quick fix: we need to look into rebuilding union power, into ownership within society, and into inequality. It’s actually a long hard slog, but I do think the four-day week is an important demand.

How do we square these kinds of ‘less work’ solutions with a more radical anti-work politics – are these things at odds with each other?

I think there are different temporalities of struggles. So on the one hand, we might be asking for higher wages, but on the other hand, we might eventually abolish the wage. I think it’s entirely possible to be saying we want a bit less work now, but in the future, we want the transformation of work or the abolition of work as we know it.

So many people have lost jobs as a result of Covid-19. Will our attitude to unemployment change at all as a result?

It took a lot of ideology to make unemployment appear as an individual failure, rather than a social problem. What that suggests is that it’s open to contestation. What Covid-19 has made us able to say is, ‘Look, the reason people don’t have jobs is not because they need to get off the sofa or whatever, it’s because the jobs have gone.’

We’ve seen the government trying to talk about unemployment in the face of the pandemic, about how people are addicted to furlough, or need to be weaned off. But I don’t think it necessarily sticks as much as it has done in the past. So, I think there’s an openness to what unemployment means now. But there is still a huge amount of stigma and shame and these things which are fundamentally social problems framed as individual failures. These kinds of attitudes run really deep in our society and challenging them isn’t easy.

How do you think attitudes need to change towards unions so that they’re accepted as a fundamental part of any organisation?

We need to see unions as playing an active role rather than just being a kind of insurance policy, basically. And I think a lot is changing. The pandemic has shown that the unions are the ones saying, ‘No, it’s not safe to go in’.

But there’s still this idea that trade unions act selfishly, that they do things that will harm the public to benefit their members. The prevalence of anti-union attitudes is something we really need to fight. And I think some of that does come down to seeing it as this thing that workplaces should have. The idea that the workers should be represented, and be able to stand up and fight for their conditions, should be seen as completely normal.

Changing people’s attitudes takes a long time, because we’re up against a really pernicious ideology. But it wasn’t that long ago that even talking about the possibility of things being different made you seem like someone who was just on another planet. [For example] Austerity was seen as the necessary choice whereas now, most people, even in the establishment will say, ‘Okay, that was a political decision we made’ and there is an openness to politics that means we can contest this stuff more. But we’re still up against it: unions face ideological attacks, even from within the Labour Party.

So, I think the popularity of this kind of ‘join a union’ meme is helpful, but we need to go beyond that. It’s not just ‘join a union’, it’s push it to be more active, push it to be more militant, get more people involved, including in sectors that have not been as historically involved.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Lost in Work is out to pre-order on Pluto Press.

Daisy Schofield is Huck’s Digital Editor. Follow her on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

A reading of the names of children killed in Gaza lasts over 18 hours

Choose Love — The vigil was held outside of the UK’s Houses of Parliament, with the likes of Steve Coogan, Chris O’Dowd, Nadhia Sawalha and Misan Harriman taking part.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Youth violence’s rise is deeply concerning, but mass hysteria doesn’t help

Safe — On Knife Crime Awareness Week, writer, podcaster and youth worker Ciaran Thapar reflects on the presence of violent content online, growing awareness about the need for action, and the two decades since Saul Dibb’s Bullet Boy.

Written by: Ciaran Thapar

A visual trip through 100 years of New York’s LGBTQ+ spaces

Queer Happened Here — A new book from historian and writer Marc Zinaman maps scores of Manhattan’s queer venues and informal meeting places, documenting the city’s long LGBTQ+ history in the process.

Written by: Isaac Muk

The UK is now second-worst country for LGBTQ+ rights in western Europe

Rainbow regression — It’s according to new rankings in the 2025 Rainbow Europe Map and Index, which saw the country plummet to 45th out of 49 surveyed nations for laws relating to the recognition of gender identity.

Written by: Ella Glossop

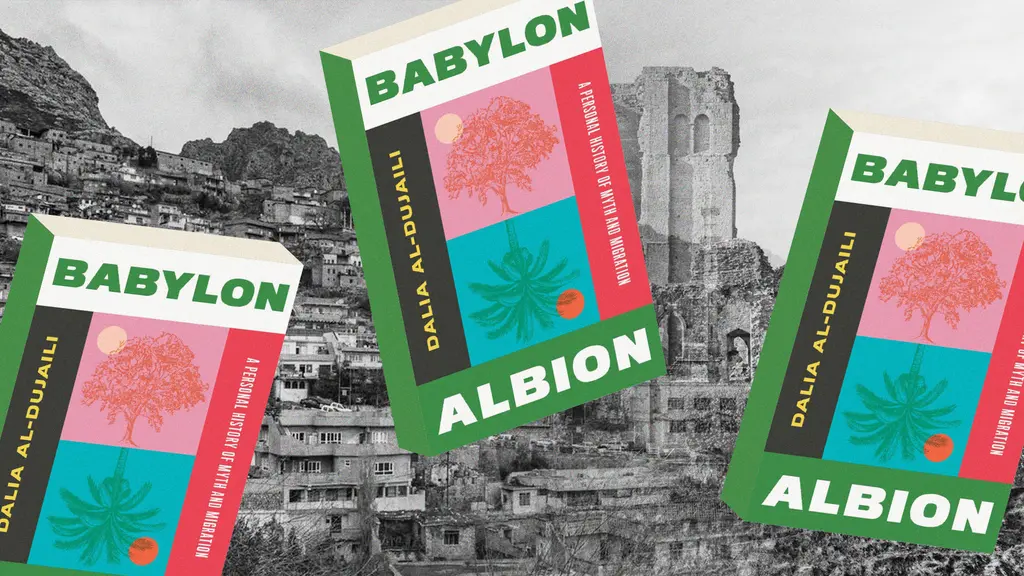

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Meet the trans-led hairdressers providing London with gender-affirming trims

Open Out — Since being founded in 2011, the Hoxton salon has become a crucial space the city’s LGBTQ+ community. Hannah Bentley caught up with co-founder Greygory Vass to hear about its growth, breaking down barbering binaries, and the recent Supreme Court ruling.

Written by: Hannah Bentley