The answer to today’s crises lies in ownership

- Text by Amelia Horgan

- Photography by Aiyush Pachnanda

From the high rents to climate crisis, ownership – who owns what and how they get to use it – structures our lives and our societies. As the concentration of power and the wealth of a new oligarchy grows, it is all too easy to slip into dismay. But just as social relations are made by people, they can be unmade by them, too.

In their new book, Owning the Future: Power and Property in an Age of Crisis (Verso Books), authors Adrienne Buller and Mathew Lawrence offer a guide to understanding the present moment and a path out of it, into a new era of ownership based on the principles of democratisation and decommodification.

To mark the release of the book, Huck spoke to the authors about ownership, the dynamics of contemporary capitalism, greenwashing, and how to change the world.

What is ownership and how does it shape the world?

Adrienne: Ownership is often discussed – in the media, among policymakers, in casual conversation – as entailing some kind of ‘natural’ right for the exclusive use and control of an asset or resource. In reality, it’s much more complex.

Ownership is about how we organise exclusive claims against the world: it is about how property has the power to concentrate, extract, and command people and assets, and in doing so, profoundly shape the societies we live in.

Property claims are not the product of some ‘natural’ and prior right. Instead, they’re a complex bundle of legal rules whose content is socially defined. Modern property rights emerged in pre-democratic societies and were intimately linked to histories of colonial violence and empire-building, and very often, those rights have been defined by the powerful in ways that reinforce and reproduce their position. The good news is that this makes them inherently contestable.

What does power look like in 21st-century capitalism?

Mathew: Power is multidimensional, contested, and complex. But at its core is the ability to act and to compel others to act in certain ways, even and perhaps particularly, if it is against their interests to do so.

To make that more concrete, take the energy crisis. People are facing a horrendous, frightening winter as bills skyrocket. Where do power and ownership come in? Because the owners of energy resources, like energy companies that own oil and gas reserves, have extraordinary leverage over society. With that leverage, comes the power to make truly eye-watering sums of money.

UK gas producers and electricity generators are estimated to make excess profits totaling as much as £170 billion over the next two years, according to the Treasury, a sum that is inseparable from how ownership of the earth and its riches are divided up and organised.

Ownership is like a magnetic forcefield that has the power to shape our society, creating winners and losers, in terms of security and dignity. But if today that power operates to mechanically extract and concentrate wealth, democratic ownership can challenge and reshape how power is exercised.

What future do we face if the way ownership is structured doesn’t change?

Mathew: Unless we reimagine how our economy is owned, it is hard to see a durable resolution of the overlapping crises confronting us. From a broken rental market to the failures of a privatised energy system to an economy that rewards those that own over those that work for a living, the corrosive combination of inequality and stagnation that is the hallmark of life in contemporary Britain will endure, worsened, too, by the cost of living crisis.

Only by addressing these issues at their root can we break with the path we’re on. That means rewiring the economy, which must in turn start with its fundamental basis: how the productive wealth of society is owned and in whose interests it operates.

Adrienne: From an ecological and climatic perspective, absent significant changes in the way we own, govern, produce and distribute [mean] things look pretty grim. A small fraction of the earth’s population not only produces several times more emissions than the poorest half but also consumes far more resources and produces more waste. All of this is sustained through the exploitation of an often invisible global working class.

In effect, this is an unprecedented enclosure of a global commons – our climate and biosphere’s ability to withstand pollution and degradation while maintaining safe conditions for life – for the benefit of a small global minority.

In OTF, you make a really important point about how the approach taken by fossil fuel companies is not merely useless or a sticking plaster, but actually a form of expansionism. Could you say more about this?

Mathew: Greenwashing tends to get criticised in a very shallow sense – that is, corporations and big finance firms are making all sorts of hollow pledges that broadly amount to hot air. By this logic, they’re an annoying and perhaps a cynical distraction, but not more than that. In reality, there’s much more at stake with corporations’ responses to the climate crisis – something Adrienne also covers in her solo book, The Value of a Whale.

Adrienne: In brief: the corporate and financial turn toward the idea of a ‘greener capitalism’ is a way of creating the contours for the transition to a decarbonised future, and staking their claims within that future, for making that future their own.

When it comes to the fossil fuel giants, the writing is on the wall: even the International Energy Agency, hardly a radical entity, has stated there are no new fossil fuels compatible with a stable climate future. Rather than exclusively funnel cash toward overt science denial, some of the oil majors have adapted their strategy. Instead, they’re focused on ‘nature-based solutions’, carbon pricing and markets, and any manner of market-based solution that can enable them to continue business as usual for as long as possible, maintain political license to operate, and create new domains for private ownership and control – for instance, by enclosing huge swathes of land for carbon offsets that may have formerly served subsistence farmers.

Courtesy Verso Books

How have ownership and capitalism changed in the past few turbulent decades?

Mathew: In recent decades, wealthy economies have undergone a process of what the political economist Brett Christophers has called ‘rentierisation’, whereby ownership of key types of scarce assets – whether it is land, intellectual property like the science behind the Covid-19 vaccine, or natural resources like gas – has become all-important, controlled by a narrow set of powerful and wealthy companies and individuals.

We are at the pinnacle of rentier capitalism, though of course, we can climb higher. Its consequences are all around: stark inequality, economic stagnation, financial dominance… The rentier turn was driven by a set of interlocking actions in which Britain was a pioneer: privatising on a massive scale, attacking organised labour to boost returns to capital over working people, reducing taxes and reshaping regulation to favour large-scale asset owners. These trends are ongoing and corrosive.

The rentier turn was itself a response to the progressive slowing down of the global economy due to deep contradictions in the organisation of capitalism. The goal was to restore profitability and power to the ownership class even as the economy slowed down. This ‘turn’ involved a whole host of inequality supercharging techniques, from mass privatisation of hitherto publicly owned wealth to new financial techniques for channeling cash to investors, such as the explosion in share buybacks.

As we enter a brutal recession, look out for new versions of this: efforts to reward asset-owners through financial engineering, tax giveaways, or policy that puts their interests above all others.

How can things change? What might a transition beyond capitalism involve?

Mathew: Fundamental to capitalism is the expropriation of the wealth that labour produces. It does this through a notionally legal and fair exchange – selling your labour for a wage – but this exchange masks the systematic transfer of value from labour to capital that is the hallmark of exploitation. Labour is compelled to do so because ordinary people are separated from the means of production. That separation is done through expropriation: the enclosure and privatisation of access to the resources we need to live a good life. Expropriation and exploitation are entwined, a dual process that gives capitalism its starkly racialised, gendered, and class-based character.

Adrienne: One way to think through the transition beyond capitalism would be, ‘What measures can halt and reverse those drivers of expropriation and exploitation?’ And, more positively, ‘What steps can we take to ensure the enormous wealth and creative capacity of society is realised equitably?’

In the book, we argue that requires three interlocking steps: democratise production, decommodify provision of life’s essentials, and expand the commons.

This might involve reimagining the company so that it is governed democratically by those who work under its rule; it might be decommodifying the fundamentals we all need to survive, from energy to housing to transport, based on a new era of democratic public ownership to replace the failed experiment of privatisation; or it could mean expanding the commons – the resources we nurture for the common good, not enclose for private gain.

Taken together, they would not only redistribute wealth, they would challenge the dominant structures of capitalism – and the unequal relations they engender – by transforming ownership.

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Owning the Future is out now on Verso Books.

Amelia Horgan is the author of Lost in Work. Follow her on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

You might like

A reading of the names of children killed in Gaza lasts over 18 hours

Choose Love — The vigil was held outside of the UK’s Houses of Parliament, with the likes of Steve Coogan, Chris O’Dowd, Nadhia Sawalha and Misan Harriman taking part.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Youth violence’s rise is deeply concerning, but mass hysteria doesn’t help

Safe — On Knife Crime Awareness Week, writer, podcaster and youth worker Ciaran Thapar reflects on the presence of violent content online, growing awareness about the need for action, and the two decades since Saul Dibb’s Bullet Boy.

Written by: Ciaran Thapar

A visual trip through 100 years of New York’s LGBTQ+ spaces

Queer Happened Here — A new book from historian and writer Marc Zinaman maps scores of Manhattan’s queer venues and informal meeting places, documenting the city’s long LGBTQ+ history in the process.

Written by: Isaac Muk

The UK is now second-worst country for LGBTQ+ rights in western Europe

Rainbow regression — It’s according to new rankings in the 2025 Rainbow Europe Map and Index, which saw the country plummet to 45th out of 49 surveyed nations for laws relating to the recognition of gender identity.

Written by: Ella Glossop

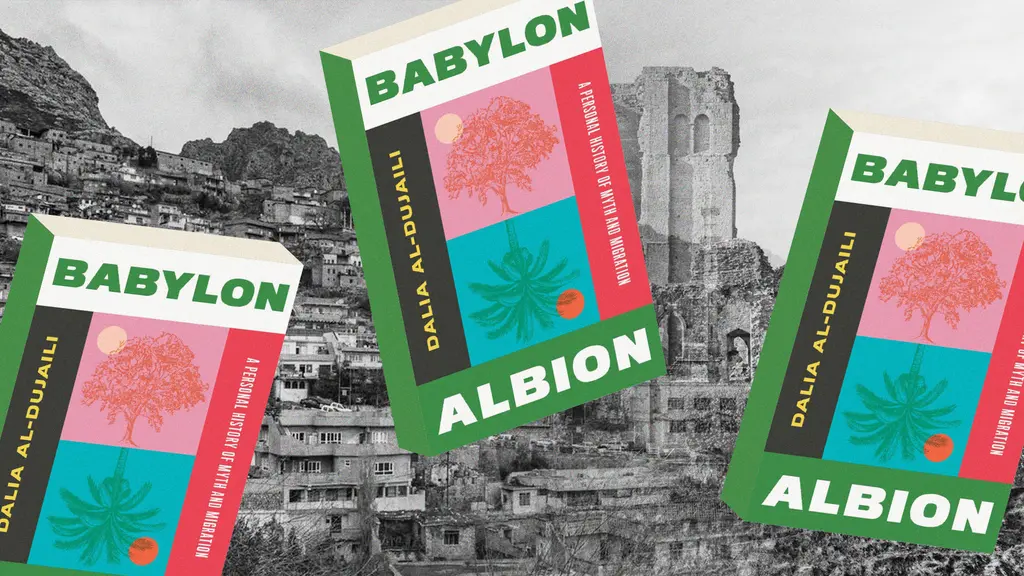

Dalia Al-Dujaili: “When you’re placeless, nature can fill the void”

Babylon, Albion — As her new book publishes, the British-Iraqi author speaks about connecting with the land as a second-generation migrant, plants as symbols of resistance, and being proud of her parents.

Written by: Zahra Onsori

Meet the trans-led hairdressers providing London with gender-affirming trims

Open Out — Since being founded in 2011, the Hoxton salon has become a crucial space the city’s LGBTQ+ community. Hannah Bentley caught up with co-founder Greygory Vass to hear about its growth, breaking down barbering binaries, and the recent Supreme Court ruling.

Written by: Hannah Bentley