Chaos and community in British photography since the ‘60s

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by Rock Against Racism. Photo by Syd Shelton, Leed 1981 (main image)

While working on Martin Parr’s first retrospective exhibition in 2018, curator and filmmaker Ralph Goertz became fascinated by the development of British documentary photography over the past 60 years. He began thinking about the importance of elevating the work of photographers who were sometimes unexplored or forgotten alongside celebrated figures like Parr and David Hurn.

With the recent publication of Facing Britain: British Documentary Photography Since the 1960s (Walter Konig), which accompanies a touring exhibition of the same name, Goertz does just this. Bringing together the work 48 photographers including James Barnor, Tish Murtha, Alys Tomlinson, and Tony Ray-Jones, Geortz explores different eras of economic expansion and decline, political movements and crises, and scenes of everyday life in Britain.

Nim and Other Stories (c) Kalepsh Lathigra

“The strength of British documentary photography is that it always starts as a reaction to political and social struggles,” says Goertz. “All protests, conflicts, financial booms, and industrial declines have shaped these photographers, their attitude and empowerment.”

Goertz also cites education, women’s empowerment, and a more inclusive society as having a deep impact on the development of the form, as photographers fight alongside the people for their voices to be heard. “Most of the photographers worked on their series as independent artists, which is very unique,” he says. “It was very impressive to see them express a special relationship or attitude on a specific issue or topic, and just doing it.”

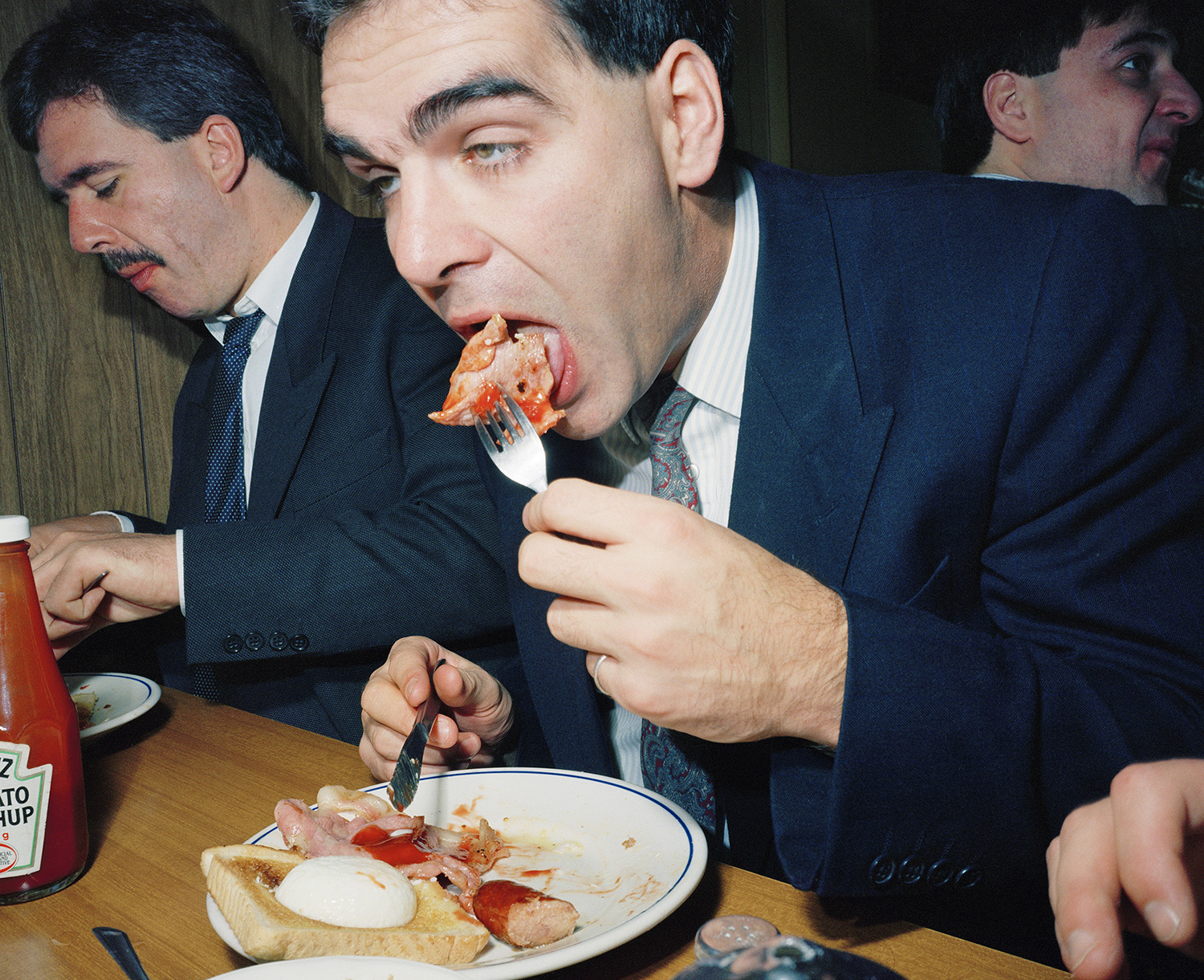

Fortunes are being made that are in line with the dreams of avarice, 1987 (c) Anna Fox

My favourite colour is yellow, 2016 (c) Kirsty Mackay

Inspired by Cornel Capa’s notion of “the concerned photographer,” many British documentary photographers have long recognised the camera as a tool for social justice. “Photographers like Mike Abrahams, Dave Sinclair, Homer Sykes, Syd Shelton and Chris Steele-Perkins are part of this group,” says Goertz.

“John Davis’s brilliant landscapes are strong photographs that can stand alongside works by Ansel Adams. But if you read the context for a photograph like ‘Ffestiniog railway, Blaenau, Ffestiniog, Snowdonia’ (1994), it punches you in the stomach. That romantic small town is toxic from nuclear materials to this day.”

Seeing himself as an outsider due to his German background and education, Goertz looks to bridge his own view of photography with those working in the UK. “I see photography as a dialogue. Some photographers are great observers while others are more active or more part of the scene,” he says.

Mr. & Mrs. Hudson. Leeds (c) Peter Mitchell

“Tom Wood’s series, Looking for Love’is a great example for being part of a community; the same with Roy Metha and his series on Harlesden, which you can read as a love letter to the multicultural community in London. There’s also John Myers’s very conceptual portraits he did in the 1970s in his West Midlands neighbourhood.”

Seeking to find a balance between the stories being told and the photographers being represented, Goertz uses the exhibitions as a way to expand the conversation and share new works. “No venue has the same show,” he says. “It’s always different, always new photographers.”

Black Copper, London, 1985 (c) Dave Sinclair

Harlesden, West London, 1989 – 1993 (c) Roy Mehta

From ‘The Last Resort. 1983-85 (c) Martin Parr

I can help, 1986-88 (c) Paul Reas

Junior Wales ballroom dancing championships. 1973 (c) David Hurn

RUC Patroling Northern Ireland football supporters, Belfast 1979 (c) Kevin O’Farrell

Facing Britain: British Documentary Photography Since the 1960s is on view at Mönchehaus Museum in Goslar, Germany, through May 1, 2022, and the Museum of Photography in Krakow, Poland, in 2022.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

You might like

Largest-Ever Display of UK AIDS Memorial Quilt Opens at Tate Modern

Grief Made Visible — Comprising hundreds of panels made by lovers, friends and chosen family, the UK AIDS Memorial Quilt returns in full for the first time since 1994 – a testament to grief, friendship and the ongoing fight against HIV stigma.

Written by: Ella Glossop

The carnival and community of New York’s block parties

Soul of the Summer — Since attending his first street party in Crown Heights two decades ago, photographer Anderson Zaca has spent his summers travelling across New York’s five boroughs, documenting over 300 in the process.

Written by: Miss Rosen

The Getty Center’s first exclusively queer exhibition opens today

$3 Bill: Evidence of Queer Lives — Running until September, it features paintings, ephemera, video and photography to highlight LGBTQ+ histories, culture and people from 1900 to the present day.

Written by: Isaac Muk

Remembering New York’s ’90s gay scene via its vibrant nightclub flyers

Getting In — After coming out in his 20s, David Kennerley became a fixture on the city’s queer scene, while pocketing invites that he picked up along the way. His latest book dives into his rich archive.

Written by: Miss Rosen

On Alexander Skarsgård’s trousers, The Rehearsal, and the importance of weirdos

Freaks and Finances — In the May edition of our monthly culture newsletter, columnist Emma Garland reflects on the Swedish actor’s Cannes look, Nathan Fielder’s wild ambition, and Jafaican.

Written by: Emma Garland

Capturing life in the shadows of Canada’s largest oil refinery

The Cloud Factory — Growing up on the fringes of Saint John, New Brunswick, the Irving Oil Refinery was ever present for photographer Chris Donovan. His new photobook explores its lingering impacts on the city’s landscape and people.

Written by: Miss Rosen